Export Restrictions and the Food Crisis

by Brandon Fuller Rising food prices, particularly prices for grains like rice, wheat, and corn, gave way to a global crisis over the past year. For many Americans, the crisis amounts to paying extra for a side of rice with their chicken masala. For the world's poorest citizens, however, the sharp increase in prices seriously hampers health and well-being.

Rising food prices, particularly prices for grains like rice, wheat, and corn, gave way to a global crisis over the past year. For many Americans, the crisis amounts to paying extra for a side of rice with their chicken masala. For the world's poorest citizens, however, the sharp increase in prices seriously hampers health and well-being.As Paul Krugman outlined in April, the factors behind rising grain prices include growing demand for meat (the production of which requires grain-based animal feed), growing demand for oil (a key input in the production and transportation of grains), some bad luck with weather, and massive public subsidies for biofuels such as the U.S. government's support for corn-based ethanol.

The crisis posed unusual challenges for middle-income countries, like India, that are also major grain exporters. In such countries, higher prices jeopardize the food security of low-income families even as they substantially boost the incomes of farmers. Faced with this predicament, India, Argentina, Russia, Vietnam, and many other countries chose to curb rising prices at the expense of farmers' incomes, imposing export restrictions on key crops such as soybeans, wheat, and rice.

As expected, the export restrictions reduced the incomes of farmers in the restricting countries. Without access to global markets and foreign buyers, domestic farmers ended up receiving lower prices and selling less than they would have in the absence of the restrictions. The restrictions did provide some relief to domestic consumers who ended up paying less and buying more than they would have in the absence of restrictions.

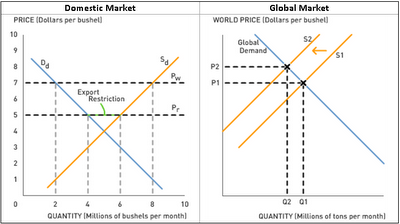

To see why, consider a graph showing the domestic supply (Sd) and demand (Dd) curves for a wheat exporter. Before the restriction, domestic consumers buy 2 million bushels of wheat per month at the going world price (Pw) of $7 per bushel, but domestic farmers sell 8 million bushels of wheat per month. The difference between domestic consumption and production represents exports to the rest of the world (6 million bushels per month). If the government restricts exports to 2 million bushels per month, the domestic price of wheat falls to $5 per bushel (Pr). After the restriction, domestic farmers sell fewer bushels (6 instead of 8 million) at lower prices and domestic consumers buy more bushels (4 instead of 2 million) at lower prices. Domestic farmers lose and domestic consumers gain.

The export restrictions may have kept food prices down in domestic markets of major grain exporters, but from a global perspective, the restrictions undoubtedly prolonged the food crisis. As major grain exporters restricted the amount of grain leaving their borders, the global supply of grains declined, leading to higher grain prices and reduced availability in the rest of the world.

The export restrictions may have kept food prices down in domestic markets of major grain exporters, but from a global perspective, the restrictions undoubtedly prolonged the food crisis. As major grain exporters restricted the amount of grain leaving their borders, the global supply of grains declined, leading to higher grain prices and reduced availability in the rest of the world.Discussion Questions

1. Recently, several major food exporters have decided to scale back their export restrictions. How will these decisions impact food consumers and farmers in the countries that are removing the restrictions? How will these decisions impact global food prices and availability?

2. Clearly, biofuel subsidies played a role in destabilizing global food markets. Even with biofuels subsidies, though, we might expect higher food prices to give farmers an incentive to bring more land into production or use existing land more efficiently. How do food export restrictions dampen those incentives?

3. How can countries ensure food security for people who are vulnerable to rising food prices without contributing to the food crisis at the global level?

Labels: Economic Development, Free Trade, Supply and Demand

1 Comments:

At 4:57 PM, November 20, 2008, Unknown

said…

Unknown

said…

While I strongly encourage the idea of utilizing natural resources for the sake of society, I believe that businesses must be regulated and careful of the consequences of the decisions they make. This article mentions specifically the use of biofuels, such as corn-based ethanol. However, as this article points out, “massive public subsidies for biofuels” have been cause for rising grain prices, among other things. Not only did the grain prices hit here at home, but “India, Argentina, Russia, Vietnam…chose to curb rising prices at the expense of farmers’ incomes.” Is it okay that high prices of grain have threatened the supply of food some families while aiding the incomes of farmers? I understand that these are the market forces of supply and demand, but we have to learn from what we’re doing with a fairly new resource like corn-based ethanol. If it will cause effects like this regularly with no planned solution, then perhaps it’s not the nation’s best option to continue on this path in this specific manner.

Post a Comment

<< Home