Rethinking Rationing

by Chrissie Deist

“There need to be some guarantees that the government is not going to take away the health care decision-making from a patient and their doctor. I think we need to start with the guarantee that there won’t be any government rationing or discrimination of any kind.”

-- Representative Eric Cantor (R-Va.)

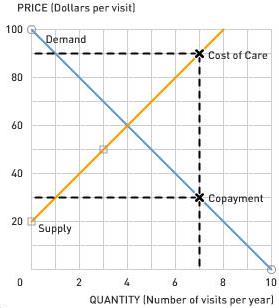

As demonstrated by the quote above, the word “rationing” doesn’t sit well with proponents of free markets. While the goal of rationing health care is to control costs by restricting insurance coverage for expensive procedures that yield relatively low benefits, doing so would also limit patients’ freedom to choose treatment options that might otherwise be available under their private insurance plans. As you learned from the basic supply and demand model, restricting the supply of a good can preclude the occurrence of transactions that could benefit both the producer and the consumer. However, the fact that the market for medical treatment is already substantially distorted by the insurance system complicates the standard supply and demand analysis.

When receiving medical treatment under most insurance plans, patients pay a copayment that accounts for only a small portion of the true cost of the treatment. Their insurance company pays the remainder, using the money it receives from monthly payments from all of its insured patients. This monthly payment is known as the insurance premium. While the monthly premium varies with different plans and individual circumstances, the amount charged is largely a function of the total number and cost of insurance claims by insured patients – as the number and cost of treatments covered by insurance companies rises, so too do the premiums paid by the insured.

While the copayment on an expensive procedure may seem like a fair price to the recipient of the treatment, those indirectly paying for the remainder of the cost in the form of high premiums may not consider it such a bargain. In economic terms, the marginal private benefit of treatment is lower than the marginal social cost paid by all the insured.

The benefit to insurance is, of course, the fact that it disperses large risks over a large number of individuals. This increases the utility of risk averse individuals who prefer paying the monthly premium as opposed to the possibility of needing serious medical care and facing enormous costs.

The benefit to insurance is, of course, the fact that it disperses large risks over a large number of individuals. This increases the utility of risk averse individuals who prefer paying the monthly premium as opposed to the possibility of needing serious medical care and facing enormous costs.An additional complication to normal cost-benefit analysis is the difficulty of putting a dollar value on life and health. While it is hard to quantify the benefit of a procedure, it is simple to consider the opportunity cost of a procedure: every dollar that is spent on one patient is a dollar that can’t be spent on another. Britain’s National Health care System uses the QALY (Quality-Adjusted Life Year) as a measure of the benefit a medical treatment will provide in terms of the number and quality of years it will add to a patient’s life. Comparing the ratios of QALYs per dollar cost across treatment options, cost-utility analysis helps economists determine the allocation of health care resources that provides the most benefit to society, also known as allocative efficiency.

Markets without distortions are allocatively efficient by nature. In efficient markets, the standard conclusions about rationing can be applied. In the market for health care, however, risk aversion leads people to demand insurance which distorts costs, benefits, and allocative efficiency. While it is beyond the scope of economic analysis to determine whether the ideas behind rationing can be transformed into successful health care policy in the U.S., it can help to illuminate the myriad of economic issues involved.

Discussion Questions

1. President Obama has talked about lowering copayments and bringing down total costs for health care coverage. Based solely on the simple graph presented above, is this a reasonable claim? How could the use of rationing help make this claim more attractive?

2. From a standard economic standpoint, insurance causes “overconsumption” of health care because the marginal benefit of treatment to the patient is often lower than the marginal cost to society. However, the benefit of care is perhaps underestimated, since it does not take into account the positive externalities of treatments like vaccines. How do positive externalities help justify this “overconsumption” in the health care market?

3. Moral hazard refers to a situation in which a person who is protected against risk might behave differently from the way he or she would behave if fully exposed to the risk. Relate this concept to the effect of insurance on health care costs. How might having health insurance affect an individual’s decision to take care of their health? How could moral hazard in the health care market potentially be discouraged?

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home