A Grand Bargain?

by Chris Makler While many Americans filled their stomachs and then emptied their wallets last week, the economic blogosphere was buzzing with the possibility that the newly elected Democratic Congress might strike a "grand bargain" with the Bush administration over the issue of Social Security reform.

While many Americans filled their stomachs and then emptied their wallets last week, the economic blogosphere was buzzing with the possibility that the newly elected Democratic Congress might strike a "grand bargain" with the Bush administration over the issue of Social Security reform.The Economist suggests that an option for such a bargain would be to combine two bipartisan proposals: one by William Gale, Jonathan Gruber, and Peter Orszag that would subsidize retirement saving for low- and middle-income households, and another by Jeffrey Liebman, Maya MacGuineas, and Andrew Samwick that would reform Social Security through benefit cuts, an increase in the payroll tax cap, mandatory personal retirement accounts, and more. Mark Thoma, Andrew Samwick, and Brad DeLong, among others, have interesting comments on the matter.

Why would a Democratic takeover of Congress make such a "grand bargain" more likely? After all, President Bush's Social Security reform package flopped, even when he had a solid Republican majority in Congress.

One possible answer is that hashing out a solution to a major problem like Social Security requires that all relevant stakeholders have strong enough bargaining positions to ensure that everyone comes out of the negotiations better off than when they went in. Other successful large-scale policy changes, like welfare reform under Bill Clinton and a Republican-led Congress, have followed this pattern. By contrast, when negotiations are held between parties who do not adequately represent larger groups, agreements can break down. For example, the various conflicts in the Middle East present a number of cases in which groups that are left out of negotiations attempt to subvert the agreements that come out of those negotiations. If the Republicans had tried last year to push through Social Security reforms that were unacceptable to Democrats, such a plan would have had difficulty withstanding the test of time, as the Democrats would have tried to implement a plan of their own.

Discussion Questions

1. What kinds of transactions involve bargaining rather than market mechanisms? What principles of economics are applicable in a bargaining situation? What elements of economic theory are not?

2. Social Security reform is often called the "third rail" of American politics. (The third rail is the electrified rail of a train track, which gives anyone who touches it a nasty shock.) Why is it such a difficult problem to solve through the political process? In other words, what economic or political forces are aligned against a "grand bargain" to solve this problem?

3. Why might politicians be more willing to tackle a difficult issue when both major political parties have significant power?

4. Suppose no bargain is reached in the next few years. As the years go on, and as the Baby Boomers start to retire, do you think the likelihood of reaching a bargain in the future will increase or decrease? Why?

One of the most exciting areas of economic research in recent years has been on the subject of bargaining. If you're interested in this kind of thing, a good place to start is Al Roth's page on bargaining at Harvard.

Labels: Bargaining, Behavioral Economics

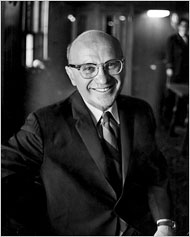

This week saw the passing of Milton Friedman, one of the most influential economists in the history of the discipline.

This week saw the passing of Milton Friedman, one of the most influential economists in the history of the discipline.