The Phillips Curve and the Federal Reserve

by William Chiu The Phillips Curve is a concept often covered in introductory macroeconomics. However, in some economic and political circles, the concept is considered outdated and useless. Some economists and commentators, such as Lawrence Kudlow, might go as far as to say that the Phillips Curve is dead. Why does the Phillips Curve command such controversy? Is it as irrelevant as some economists claim?

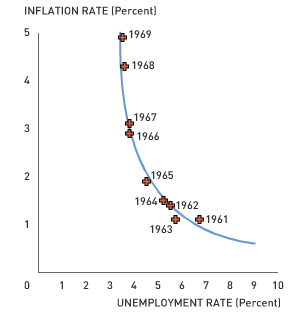

The Phillips Curve is a concept often covered in introductory macroeconomics. However, in some economic and political circles, the concept is considered outdated and useless. Some economists and commentators, such as Lawrence Kudlow, might go as far as to say that the Phillips Curve is dead. Why does the Phillips Curve command such controversy? Is it as irrelevant as some economists claim?The traditional Phillips Curve is the trade-off between the inflation rate and the unemployment rate. Many economists in the 1960s thought that the Federal Reserve or Congress could permanently lower the unemployment rate by increasing the inflation rate. The trouble is, the traditional Phillips Curve violates one of the central tenets of economics: the classical dichotomy. According to the classical dichotomy, nominal variables do not affect real variables. Consider a simple example:

I hold a bag of apples that weighs 5 pounds. The weight (i.e., the force exerted on my arm) is a real variable and the unit of measurement (i.e., pounds) is a nominal variable. Suppose the U.S. government passes a new law that says all measurements must conform to the metric system. Now the same bag of apples weighs 2.27 kilograms. Notice that the nominal variable (how the weight is measured) has absolutely no effect on the real variable (the force exerted on my arm).

The traditional Phillips Curve is in direct contradiction of the classical dichotomy. The Phillips Curve implied that the government could effectively reduce the unemployment rate (a real variable) by changing how fast overall prices are growing in the economy (a nominal variable). Though the traditional Phillips Curve held up well in the 1960s, the 1970s would usher in the downfall of the traditional Phillips Curve.

In the 1970s, the trade-off between the unemployment rate and the inflation rate seemed to fall apart. The United States experienced soaring overall prices and rising unemployment. In other words, there appeared to be an upward-sloping relationship between the inflation rate and unemployment rate. Due to this fact, many economists declared the Phillips Curve to be dead.

Due to the abrupt change in the correlation between inflation and unemployment, several theories were proposed as alternatives to the Phillips Curve. These theories include the Real Business Cycle (RBC), Rational Expectations, and Monetarism. Often times these theories are called “New Classical” economics because they promote the classical dichotomy.

Under heavy pressure from competing theories and empirical evidence, a new school of thought known as “New Keynesian” economics sought microeconomic foundations for the Phillips Curve. Edmund Phelps, the Nobel Laureate in 2006, augmented the traditional Phillips Curve by adding the critical role of expectations. Under the expectations-augmented Phillips Curve model, a trade-off between inflation and unemployment does exist but only in the short run. According to the model, inflation expectations adjust to return the economy to its natural rate of unemployment (i.e., an unemployment rate consistent with non-accelerating inflation). George Akerlof, the Nobel Laureate in 2001, provided behavioral explanations for the trade-off. Subsequent works by economists, such as David Romer and Greg Mankiw, provided additional microeconomic foundations for a short-run trade-off.

Through all the intellectual turmoil, most economists agree on the following:

1. There is a short-run trade-off between the inflation rate and the unemployment rate.

2. In the long run, the inflation rate adjusts to restore the natural rate of unemployment. Hence, policy makers cannot permanently push unemployment below its natural rate by permanently increasing the inflation rate.

How well does the modern Phillips Curve describe the real world, and do practitioners actually use the modern Phillips Curve? James Stock and Mark Watson, authors of a famous introductory econometrics textbook and well-respected econometricians, empirically showed that the modern Phillips Curve bested all other alternatives in terms of forecasting inflation. Ben Bernanke, chairperson of the Federal Reserve, professed publicly here and here on the importance of the modern Phillips Curve in the Fed's inflation forecasts, which ultimately influence monetary policy.

The Phillips Curve has changed over the past 40 years, but it is very much alive as a reference for monetary policymakers.

Discussion Questions:

1. Go to the Bureau of Labor Statistics web site and pull data on the national unemployment rate and the CPI inflation rate. For your convenience, I have included the spreadsheet here. Does there appear to be a trade-off between inflation and unemployment between January 2001 and December 2001?

2. Does there appear to be a trade-off between January 1997 and October 2007?

3. Why do you think an increase in the inflation rate decreases the unemployment rate in the short run? Why do you think a decrease in the unemployment rate increases the inflation rate in the short run?

Labels: Expectations, Inflation, Monetary Policy, Phillips Curve, Unemployment

Two of the bestselling economics textbooks are by Paul Krugman of Princeton and Greg Mankiw of Harvard. Reading the textbooks, it’s not abundantly clear that the authors would disagree about much: both illustrate supply and demand, the gains from trade, the deadweight loss caused by taxes, the market failure that results from the existence of externalities.

Two of the bestselling economics textbooks are by Paul Krugman of Princeton and Greg Mankiw of Harvard. Reading the textbooks, it’s not abundantly clear that the authors would disagree about much: both illustrate supply and demand, the gains from trade, the deadweight loss caused by taxes, the market failure that results from the existence of externalities.

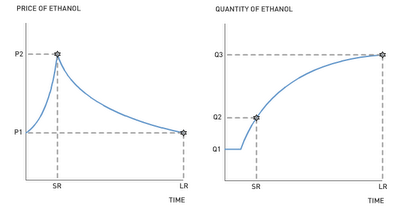

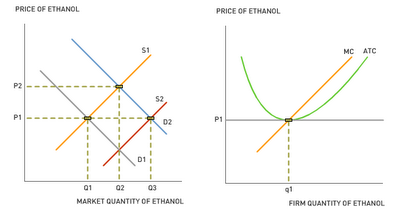

Notice that economic profits converge to zero in the long run. As explained by most textbooks, zero economic profit does not mean that ethanol producers barely have enough to eat. Zero economic profit means that ethanol producers are earning incomes that compensate them for the next best salary they had to give up to go into producing ethanol.

Notice that economic profits converge to zero in the long run. As explained by most textbooks, zero economic profit does not mean that ethanol producers barely have enough to eat. Zero economic profit means that ethanol producers are earning incomes that compensate them for the next best salary they had to give up to go into producing ethanol.