Would You Rather Receive $250 or an iPod?

by Chris Makler Telling everyone else how to rationally allocate their money is a pastime enjoyed by economists and non-economists alike. The holiday season, though, always seems to bring about the same piece of advice from economists: give cash, not stuff.

Telling everyone else how to rationally allocate their money is a pastime enjoyed by economists and non-economists alike. The holiday season, though, always seems to bring about the same piece of advice from economists: give cash, not stuff.The argument is compelling, at least theoretically. Which would you rather receive as a gift--$250 or an iPod costing $250? If you got the cash, you could always buy the iPod, or you could buy something you liked better. Therefore, the cash must be at least as good as the iPod. Therefore, the cash must be a better gift; QED.

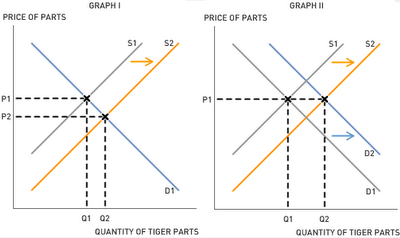

There is at least some empirical support for this argument. From student surveys, economist Joel Waldfogel found that "on average, a dollar that people spend for themselves creates nearly 20 percent more satisfaction than a dollar that someone else spends on them." If this is true of the entire population, Waldfogel estimates that the "deadweight loss of Christmas"--that is, the loss of consumer satisfaction caused by misallocated Christmas gifts--is somewhere between $2 billion and $9 billion per year. (Waldfogel recently wrote a piece about this research in Slate; it was also written up in The Economist a few years ago.)

So why do people give gifts? An answer may lie in a seemingly unrelated area of economics: wages and compensation. Consider the case of Arcnet, a telecom company in

Now, the same logic applies to Arcnet's BMW offering as to holiday gifts. Suppose it costs $800 per month to lease a BMW 3 series and pay for the other goodies they throw in. Wouldn't Arcnet be able to retain even more workers if it just gave everyone an $800-per-month raise? Then they could lease the car if they wanted to, or get something else they liked better. Yet it's very possible that employees value a BMW more than they would value an additional $800 per month.

Economist Robert Frank suggests that the answer to this paradox may lie in something that goes against the grain of standard consumer theory: people may actually like being constrained to accept a particular gift, rather than being able to "optimally" allocate an equivalent amount of money for themselves. Why? Because sometimes it's nice to get something that your rational self knows you shouldn't choose. As Frank put it in a 1999 New York Times piece, speaking of Arcnet's BMW offer,

Perhaps you'd find it awkward to tell your Depression-era parents that you'd bought a car costing twice as much as a Toyota Camry. Or you may worry that your neighbors would think you were putting on airs if you bought yourself a new BMW. Or perhaps you've wanted to make such a purchase but your spouse insists on remodeling the kitchen instead.

In other words, you can get as a gift something that you couldn't justify buying for yourself, even though you would like to have it.

Both Waldfogel and Frank concentrate on one-way gift giving: Arcnet's employees, after all, don't get Arcnet gifts in exchange for their BMWs. And indeed, if only one person is giving a gift, then cash may very well be king. But if gifts are being exchanged, then a host of new considerations come into play.

Suppose we take Waldfogel's conclusion to heart. To do away with the feared deadweight loss of Christmas, everyone gets everyone cash. Does this make sense? In some cases, almost certainly not--consider the case of a husband and wife who write each other checks from their joint checking account. But more complex issues arise in less straightforward cases. Here are some that I've thought about. Can you think of others?

1. What about parity? If you give someone $20 and they give you $40, what does that mean? Does it in fact make you feel guilty and the other person feel insulted--something that wouldn’t happen if you’d exchanged, say, a $20 necktie for a $40 bottle of wine, both with the price tags removed? (After all, since prices vary from store to store, then in the latter case there’s a non-zero probability that you paid the same amount, even if their worth is different.)

2. What happens when gifts are exchanged more than once? Suppose last year you gave someone $20 cash and they gave you $40 cash; how much should you give them this year? Do you match their $40, or raise it? Does it become like an arms race? (And if, in equilibrium, you give each other the same amount, doesn’t that just leave everyone where they started, but worse off because of the stress and uncertainty?)

3. When non-cash gifts are given, they can be compared on multiple dimensions, making it difficult to say who gave a “more valuable” gift. One may be expensive but standard (jewelry); another might be very inexpensive but heartfelt (a framed kindergarten picture saying “World’s Best Dad”). But cash has only one dimension, making comparisons between gifts easy. Are the benefits of cash in terms of flexibility outweighed by the costs of awkward interpersonal comparisons?

Labels: Behavioral Economics