Who Says There's No Such Thing as a Free Lunch

by Kasie R. Jean One of the most popular sayings associated with the “dismal science” of economics is “There’s no such thing as a free lunch.” The major idea behind this phrase is that even if you aren’t given a bill to pay, there is always an implicit cost associated with any action.

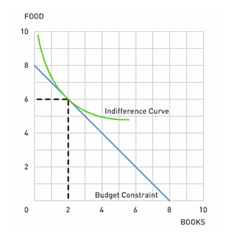

One of the most popular sayings associated with the “dismal science” of economics is “There’s no such thing as a free lunch.” The major idea behind this phrase is that even if you aren’t given a bill to pay, there is always an implicit cost associated with any action.The economic concept supporting this statement is that of opportunity cost, which is defined as the best foregone alternative. Simply stated, it’s what you give up in order to do something else. Consider the following example: you have $10 that you can either spend on a movie or a pizza. The opportunity cost of going to the movie is therefore the pizza that you give up by attending the movie, and vice versa.

But what about when a good is free to consume? What is the opportunity cost in this situation? Usually in cases like this, the opportunity cost is associated with the value of your time or some other implicit cost. For example, if you work hourly, the time it takes to wait in line for a “free” offer is time that you could’ve spent working and earning money; “free” in this case simply means that there is no explicit monetary cost, but it says nothing about the implicit costs of waiting for the item. Another common example is when you receive a “free” weekend getaway, but the cost is that you have to sit through a 2-hour sales pitch with a timeshare organization.

I was thus astonished when I received something truly for free a few weeks ago at Auntie Annie’s pretzel shop. I was at the mall with my friend when the two of us realized we were getting pretty hungry. Wanting to avoid eating a fast-food meal at the food court, we decided to each grab a pretzel at Auntie Annie’s to hold us off for awhile. As we were waiting in line, one of the workers started giving out samples. My friend suggested that we try them since the line was pretty long and we were quite hungry. As I walked over to receive the samples and my friend stayed in line, the worker also instantly handed me a coupon: BUY ONE PRETZEL, GET ANOTHER ONE FREE. Having already committed to wait in line to purchase two pretzels before I got the coupon—it was my friend’s birthday so the two pretzels were on me—I actually received a free pretzel! After consulting with some other economists, none of us could find an implicit cost that I incurred in order to receive the free pretzel (though you could argue that my time to write this blog post is an after-the-fact cost associated with the pretzel purchase). In short, who says there’s no such thing as a free lunch?

Discussion questions:

1. Can you think of a time in your life where you actually received something for free? That is, there were no explicit monetary costs or implicit opportunity costs.

2. If I was just passing by Auntie Annie’s and received the coupon, why would the second pretzel not be free? What opportunity costs would be associated with using this coupon in that case?

3. Suppose you have a “Buy 10 pretzels, Get One Free” card for Auntie Annie’s. Does it distort your behavior in any way? Is the 11th pretzel actually free?

Labels: Opportunity Cost, Tradeoffs