Do You "Appreciate" Wendy's Super Value Menu?

by Kasie R. Jean

Despite your possible love for the Double Stack burger found on Wendy's $.99 Super Value Menu, the claim made in a recent Wendy's commercial that the burger "appreciates" in value after being purchased is seriously flawed on many levels according to standard economic theory.

Of the many economic fallacies in the commercial, the immediate one that comes to mind is the mix-up between the notions of appreciation and consumer surplus. Recall from your introductory economics courses that consumer surplus is the difference between what a consumer is willing to pay for a good and what he or she actually pays for it. Obviously, you would never buy something if its valuation to you as a consumer was less than the price you must pay. Therefore, according to standard economic theory, consumer surplus must always be at least zero—though it is typically positive for an individual consumer since it is unlikely that you actually pay the true valuation for any good you purchase.

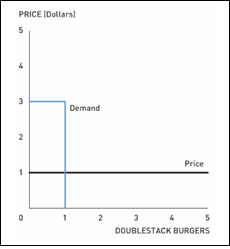

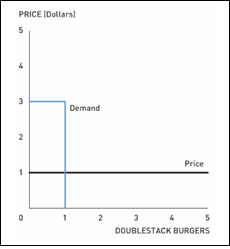

That said, it is not surprising that the "Student" in the commercial won't accept exactly what he paid for the burger since that is not his true valuation of the good. For example, it's possible that his demand curve is of the following shape:

This demand curve implies that Student will pay up to $3 for one Double Stack burger, but then nothing beyond that. This also represents his value for the first Double Stack burger. In this case, Student would receive roughly $2 (= $3 – $1) in consumer surplus by purchasing the Double Stack burger for nearly $1. Obviously, there are an infinite number of possibilities for Student's demand curve, but the one thing we know for certain is that his value of the Double Stack burger is AT LEAST the cost of the burger—but there is nothing preventing his valuation from being higher.

This demand curve implies that Student will pay up to $3 for one Double Stack burger, but then nothing beyond that. This also represents his value for the first Double Stack burger. In this case, Student would receive roughly $2 (= $3 – $1) in consumer surplus by purchasing the Double Stack burger for nearly $1. Obviously, there are an infinite number of possibilities for Student's demand curve, but the one thing we know for certain is that his value of the Double Stack burger is AT LEAST the cost of the burger—but there is nothing preventing his valuation from being higher.

Thus, the idea that Student would not accept a dollar in exchange for his burger has absolutely nothing to do with the proposed "appreciation" of the burger—in other words, Student's valuation of the Double Stack burger has not changed. Rather, this scenario is more reasonably explained by the gains in trade that the buyer receives from purchasing the good at a given price below his private valuation.

Discussion Questions

1. In economics, the notion of a shoe-leather cost—the cost to consumers of actually going to wherever the good is being sold—often plays a role in consumer and producer theory. How would your willingness to accept a dollar for a Double Stack burger change depending on whether you are currently at Wendy's or at home a few miles from the nearest Wendy's?

2. How would this discussion change if Wendy's was able to practice perfect (or first degree) price discrimination?

3. Wendy's often claims that their burger is underpriced and is therefore a value buy. If this were truly the case, why do we not see secondary markets for this good? Is Wendy's really charging the right price?

4. The endowment effect is the idea that people value a good or service more once their property right to it has been established. Is this example of such an effect? Why or why not?

Of the many economic fallacies in the commercial, the immediate one that comes to mind is the mix-up between the notions of appreciation and consumer surplus. Recall from your introductory economics courses that consumer surplus is the difference between what a consumer is willing to pay for a good and what he or she actually pays for it. Obviously, you would never buy something if its valuation to you as a consumer was less than the price you must pay. Therefore, according to standard economic theory, consumer surplus must always be at least zero—though it is typically positive for an individual consumer since it is unlikely that you actually pay the true valuation for any good you purchase.

That said, it is not surprising that the "Student" in the commercial won't accept exactly what he paid for the burger since that is not his true valuation of the good. For example, it's possible that his demand curve is of the following shape:

This demand curve implies that Student will pay up to $3 for one Double Stack burger, but then nothing beyond that. This also represents his value for the first Double Stack burger. In this case, Student would receive roughly $2 (= $3 – $1) in consumer surplus by purchasing the Double Stack burger for nearly $1. Obviously, there are an infinite number of possibilities for Student's demand curve, but the one thing we know for certain is that his value of the Double Stack burger is AT LEAST the cost of the burger—but there is nothing preventing his valuation from being higher.

This demand curve implies that Student will pay up to $3 for one Double Stack burger, but then nothing beyond that. This also represents his value for the first Double Stack burger. In this case, Student would receive roughly $2 (= $3 – $1) in consumer surplus by purchasing the Double Stack burger for nearly $1. Obviously, there are an infinite number of possibilities for Student's demand curve, but the one thing we know for certain is that his value of the Double Stack burger is AT LEAST the cost of the burger—but there is nothing preventing his valuation from being higher.Thus, the idea that Student would not accept a dollar in exchange for his burger has absolutely nothing to do with the proposed "appreciation" of the burger—in other words, Student's valuation of the Double Stack burger has not changed. Rather, this scenario is more reasonably explained by the gains in trade that the buyer receives from purchasing the good at a given price below his private valuation.

Discussion Questions

1. In economics, the notion of a shoe-leather cost—the cost to consumers of actually going to wherever the good is being sold—often plays a role in consumer and producer theory. How would your willingness to accept a dollar for a Double Stack burger change depending on whether you are currently at Wendy's or at home a few miles from the nearest Wendy's?

2. How would this discussion change if Wendy's was able to practice perfect (or first degree) price discrimination?

3. Wendy's often claims that their burger is underpriced and is therefore a value buy. If this were truly the case, why do we not see secondary markets for this good? Is Wendy's really charging the right price?

4. The endowment effect is the idea that people value a good or service more once their property right to it has been established. Is this example of such an effect? Why or why not?

Labels: Gains from Trade, Inflation, Supply and Demand, Welfare Analysis