The Dollar Is Sinking, but What Does That Mean to Me?

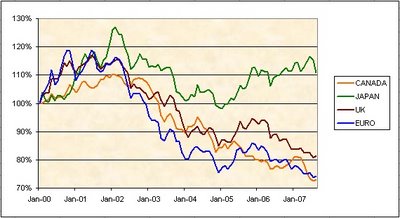

by Chris BuzzardThe graph below illustrates how the U.S. dollar has performed relative to four major currencies (the euro, British pound, Canadian dollar, and Japanese yen) over the last decade relative to their January 1, 2000 values. But what effect do declining exchange rates really have on us?

At the consumer level, it's fairly simple—a weaker dollar means our purchasing power is weaker when buying foreign goods. Effectively, imported goods become more expensive, since the U.S. dollar can buy fewer euros, for example. However, there is another side to this story, because it also means that U.S. goods are cheaper to foreign consumers. This is one of those things that sounds bad, but depending on who you are, can actually be quite good. If you are a U.S. firm, a weaker dollar can be beneficial because it enables foreign consumers to buy more of your products.

At the consumer level, it's fairly simple—a weaker dollar means our purchasing power is weaker when buying foreign goods. Effectively, imported goods become more expensive, since the U.S. dollar can buy fewer euros, for example. However, there is another side to this story, because it also means that U.S. goods are cheaper to foreign consumers. This is one of those things that sounds bad, but depending on who you are, can actually be quite good. If you are a U.S. firm, a weaker dollar can be beneficial because it enables foreign consumers to buy more of your products.In fact, a weaker U.S. dollar is beneficial to U.S. multinationals in a more fundamental way. When a firm sells abroad, it generally sells its goods at a price denominated in the currency of the foreign country it is dealing in. Ultimately, the U.S. firm's shareholders care about dollar-denominated revenues and profits. A declining U.S. dollar means that a firm's euro-, pound-, or yen-denominated revenues can be exchanged for more U.S. dollars than they could have been when the U.S. dollar was stronger. Hence, a U.S. multinational that transacts in several currencies benefits when the dollar declines because its foreign revenues are worth more on a U.S. dollar basis, and vice versa. For example, in the mid- to late 1990s, many U.S. multinationals selling in Asia experienced phenomenal sales growth, yet their profits grew only modestly. During this period, the Asian currencies weakened, decreasing the worth of these firms' revenues in U.S. dollars. Hence, record-breaking unit sales translated into only modest profits in terms of U.S. dollars.

Discussion Questions

1. Who has a greater interest in a strong U.S. dollar—U.S. consumers or U.S. producers?

2. What sort of tax implications may exist for U.S. multinationals as a result of fluctuating exchange rates, especially a weaker U.S. dollar?

3. If a firm owes €100,000 to a German supplier due in 30 days (an account payable), does it prefer that the U.S. dollar strengthen or weaken relative to the euro?

4. Suppose a different firm is owed ₤88,000 from a UK customer due in 45 days (an account receivable). The spot exchange rate is $2.01/₤. How much (in U.S. dollars) would the firm receive if it were paid today? Discuss the gain or loss implications for the firm if the money isn't received for 45 days and the exchange rate moves to either $2.10/₤ or $1.90/₤ during that time.

Labels: Exchange Rate, Finance, International Economics

The value of the U.S. dollar (USD) is falling against a number of foreign currencies, including the Canadian dollar (CAD), also known as the loonie. As the dollar weakens against the loonie, imports from Canada, including illegal drugs like marijuana, become more expensive. As American dope-smokers get priced out of the market for high-quality Canadian marijuana, they increasingly turn to lower-quality Mexican varieties and, as this

The value of the U.S. dollar (USD) is falling against a number of foreign currencies, including the Canadian dollar (CAD), also known as the loonie. As the dollar weakens against the loonie, imports from Canada, including illegal drugs like marijuana, become more expensive. As American dope-smokers get priced out of the market for high-quality Canadian marijuana, they increasingly turn to lower-quality Mexican varieties and, as this  The Federal Open Market Committee (

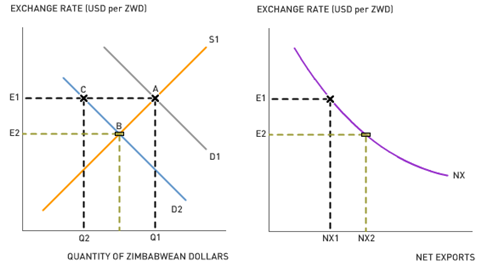

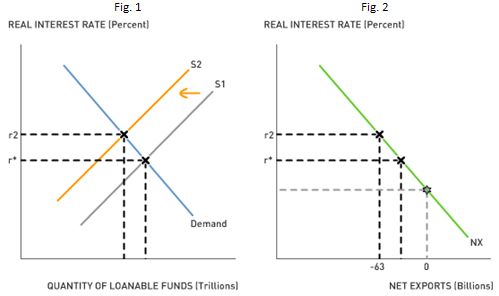

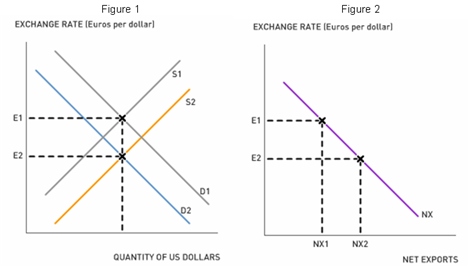

The Federal Open Market Committee ( A depreciation of the U.S. currency will make U.S. exports relatively inexpensive for foreigners while making imports from foreign countries relatively expensive for Americans. A decrease in the interest rate causes an increase in net exports and reduces the size of the U.S. trade deficit. Figure 2 shows the relationship between the exchange rate and net exports. Since net exports are a component of total spending in the U.S. economy, the Fed's rate cut provides two boosts to aggregate spending: (1) the rate cut stimulates consumption and investment because the cost of borrowing decreases; and (2) the rate cut stimulates net exports due to U.S. dollar depreciation. By cutting the target fed funds rate, the Fed intends to prop up spending and growth at a time when tightening credit conditions threaten to slow or reverse the growth of economic output.

A depreciation of the U.S. currency will make U.S. exports relatively inexpensive for foreigners while making imports from foreign countries relatively expensive for Americans. A decrease in the interest rate causes an increase in net exports and reduces the size of the U.S. trade deficit. Figure 2 shows the relationship between the exchange rate and net exports. Since net exports are a component of total spending in the U.S. economy, the Fed's rate cut provides two boosts to aggregate spending: (1) the rate cut stimulates consumption and investment because the cost of borrowing decreases; and (2) the rate cut stimulates net exports due to U.S. dollar depreciation. By cutting the target fed funds rate, the Fed intends to prop up spending and growth at a time when tightening credit conditions threaten to slow or reverse the growth of economic output.