America's Looming Liquidity Trap

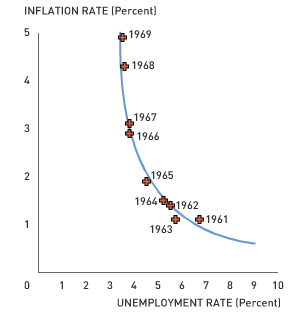

by Michael Enriquez In October 2008, the US unemployment rate hit 6.5%, a 14-and-a-half year high, as announced by the Labor Department. This lofty rate is likely to increase in the coming months in the wake of the ongoing financial crisis and adjustments in the real estate market. It also comes despite two 50 basis point cuts in the target federal funds rate made by the Federal Reserve during that month. These interest rate reductions brought the target fed funds rate down to 1%, a very low target rate by historical standards and close to the nominal rate floor of 0%. The Federal Reserve therefore finds itself in the thorny situation of having only 100 basis points left to work with for possible target rate cuts. (Note that a basis point represents 1/100th of a percentage point, so 1% is 100 basis points.)

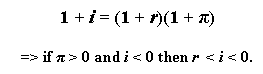

In October 2008, the US unemployment rate hit 6.5%, a 14-and-a-half year high, as announced by the Labor Department. This lofty rate is likely to increase in the coming months in the wake of the ongoing financial crisis and adjustments in the real estate market. It also comes despite two 50 basis point cuts in the target federal funds rate made by the Federal Reserve during that month. These interest rate reductions brought the target fed funds rate down to 1%, a very low target rate by historical standards and close to the nominal rate floor of 0%. The Federal Reserve therefore finds itself in the thorny situation of having only 100 basis points left to work with for possible target rate cuts. (Note that a basis point represents 1/100th of a percentage point, so 1% is 100 basis points.)The fed funds rate cannot go below 0% because a transaction at a negative nominal rate implies a negative nominal cost of borrowing funds. Furthermore, that implies a positive nominal payoff to the borrower and a positive nominal loss to the lender. Under typical, positive rates of inflation, the real costs and payoffs are amplified. This is shown in the following Fisher equation where i is the nominal interest rate, r is the real interest rate, and

is the inflation rate:

is the inflation rate:

This floor for the nominal fed funds rate brings up the very real possibility that the US will soon be mired in a liquidity trap—a situation in which "the monetary authority is unable to stimulate the economy with traditional monetary policy tools." One explanation for this weakness of monetary policy comes from the analysis on the real interest rate given above. In difficult economic times, why would financial institutions take on the risk of lending out money to a borrower who may default on the loan when the real return on even a fully repaid loan is negative!

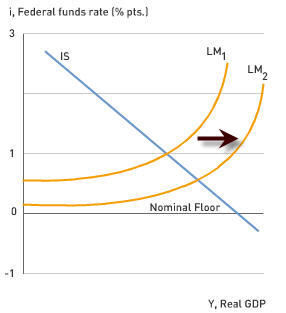

An excellent source on how our nation might remedy its liquidity trap is given by the 2008 Nobel Laureate in Economic Sciences, Paul Krugman. His 1999 article "Thinking About the Liquidity Trap" offered policy solutions for springing the Japanese economy from the type of liquidity trap that now threatens the United States. Krugman's figure 1 from that paper shows a nice IS-LM example of the ineffectiveness of monetary policy. Wikipedia provides a good introduction to the IS-LM model. Below I present a modified version of Krugman's figure 1, in the context of current US interest rates, to represent traditional monetary expansion with a looming liquidity trap.

An economy may also happen to face declining consumption expenditures, as the US currently does, due to concerns about a rising unemployment rate, which can result in lower exogenous consumption and a falling marginal propensity to consume. In that case, the resulting leftward movements of the IS curve make monetary policy even less effective. Krugman's solution to the scenario is to have the monetary authorities credibly commit to sustained higher future inflation. The expectation that such higher inflation will eat away at the purchasing power of cash holdings should convince consumers to ramp up their spending and move the IS curve rightward.

President-elect Obama and the new Congress will undoubtedly undertake expansionary fiscal policy to attempt to move the IS curve rightward. However, our already massive national debt and the likelihood of waste involved in government spending, support Krugman's solution. Our newly elected officials and the Federal Reserve Board are facing unenviable policy choices.

Discussion Questions

1. Suppose that you were in control of US fiscal and monetary policy. What policies, if any, would you implement to improve US economic conditions?

2. Do you believe that America will soon face a liquidity trap? Why or why not?

3. The International Monetary Fund forecasts that the world's rich economies will collectively experience economic contraction for the first time since World War II. When was the last time America faced a liquidity trap? What circumstances led to that liquidity trap environment?

Labels: Expectations, Fiscal Policy, Global Economic Watch, Interest Rate, Lending, Macroeconomics, Monetary Policy, Money, Unemployment