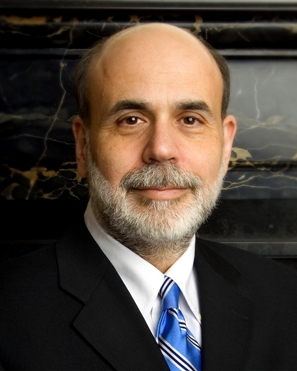

Fed Chairman Bernanke Chosen as Time Magazine's Person of the Year

by Michael Enriquez In a December 16, 2009 article, Michael Grunwald details the reasoning behind Time Magazine’s choice of Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke for Person of the Year. The article delves into Bernanke’s background such as his working class roots and the consensus that he is “a leading scholar of the Great Depression.” It also details the unique nature of the crises of 2007-2008 to which the Fed responded in creative and beneficial ways.

In a December 16, 2009 article, Michael Grunwald details the reasoning behind Time Magazine’s choice of Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke for Person of the Year. The article delves into Bernanke’s background such as his working class roots and the consensus that he is “a leading scholar of the Great Depression.” It also details the unique nature of the crises of 2007-2008 to which the Fed responded in creative and beneficial ways.Chairman Bernanke is currently awaiting a Senate vote to be confirmed for another term as Fed chairman. The vote is being held up by a Senator from the far left and another from the far right. The Time article is largely critical of those who oppose Bernanke, portraying them as nitpicky demanders of perfection who fail to realize that the Federal Reserve’s actions over the past two years most likely “prevented an economic catastrophe.” It is apparent that the Fed, like most people caught up in benefiting from the bubbles of those years, took too long to recognize the danger signs. Yet, the desire to criticize and rein in the Fed’s power now that the crises are largely history is short-sighted and will be harmful to long-run inflation rates. Most economics textbooks cover the extensive research that shows that greater central bank independence goes along with more stable and lower inflation rates.

As Bernanke is quoted in the article, "We came very, very close to a depression ..." That is because in the fall of 2008, the collapse of the financial sector and asset prices looked remarkably similar to the events that marked the start of the Great Depression. However, thanks largely to the bold actions of Bernanke’s Fed, the US experienced a severe recession rather than a depression. That distinction is significant and reason enough for the awarding of Time Magazine’s honor. Grunwald’s article gives evidence that Bernanke’s knowledge and research into the Depression made him the perfect man to hold one of the most powerful positions for influencing the world economy. As written by Grunwald, “He didn't just reshape U.S. monetary policy; he led an effort to save the world economy.”

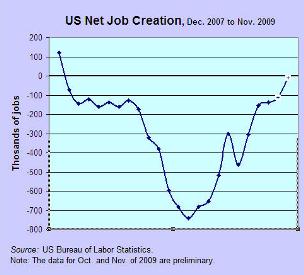

Admittedly, the severe recession has caused significant hardship to billions of people. However, based on economists’ consensus definition of recession, the US economy has been in recovery and thus out of recession for several months now. Indeed, the figure to the right shows a picture of an economy that will most likely experience positive net job creation in coming months. Such positive net job creation has not occurred since the recession began in December 2007. This scenario looks much rosier than could have been hoped for back in the fall of 2008. This is an important reason why Bernanke is expected to be confirmed for another term:

Admittedly, the severe recession has caused significant hardship to billions of people. However, based on economists’ consensus definition of recession, the US economy has been in recovery and thus out of recession for several months now. Indeed, the figure to the right shows a picture of an economy that will most likely experience positive net job creation in coming months. Such positive net job creation has not occurred since the recession began in December 2007. This scenario looks much rosier than could have been hoped for back in the fall of 2008. This is an important reason why Bernanke is expected to be confirmed for another term:

Finally, Bernanke’s critics need to understand that macroeconomics is not a true science. Despite the mathematical rigor required to publish articles in the field, macroeconomists cannot perform true experiments with a nation’s economy. Therefore, there is no comparison “control group” of a US economy run by someone who chose not to bailout AIG or who refused to dramatically expand the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet with risky assets. We will never know with any respectable precision what might have happened if it had not been for Bernanke’s bold leadership.

Perhaps someday a scientific genius will invent a time machine so that Bernanke’s critics can go back to the early 1930s to experience a collapsed economy. Most economists agree that the experience of those years is the best counterexample to show what we would have experienced without bold action by the Fed and our elected officials. Let the critics be reminded that the demand for perfection is all too often the enemy of good governance.

Discussion Questions

1. What is your reaction to Time Magazine’s choice of Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke for Person of the Year? Why?

2. Suppose that you were able to cast a vote in the Senate on Bernanke’s reappointment. How would you vote? Why?

3. Imagine you were currently chairperson of the Fed. What, if anything, would you be doing differently?

4. Do you approve or disapprove of the movement to rein in the power of the Federal Reserve? Explain.

Labels: Business Cycle, Macroeconomics, Monetary Policy, Recession

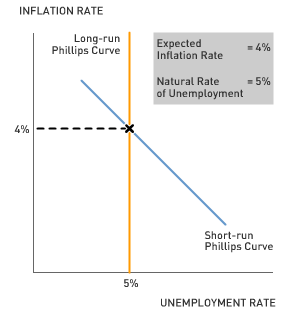

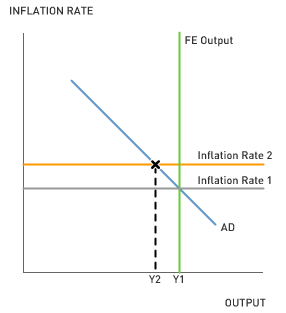

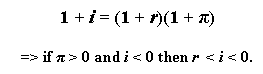

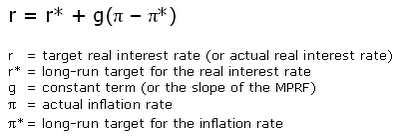

is the inflation rate:

is the inflation rate:

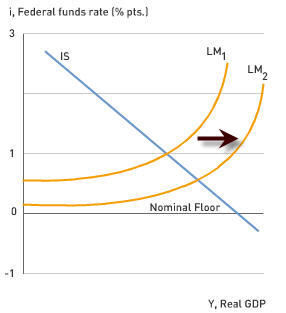

Of course, the MPRF above is just one example, and there are other examples (such as the

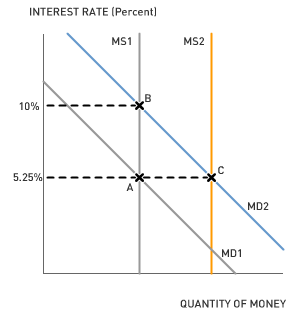

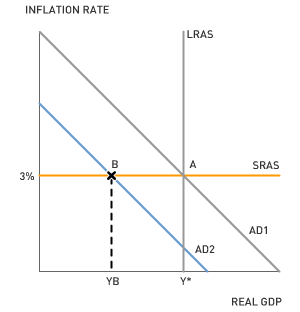

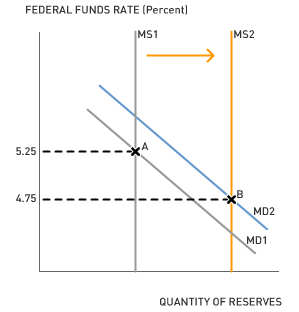

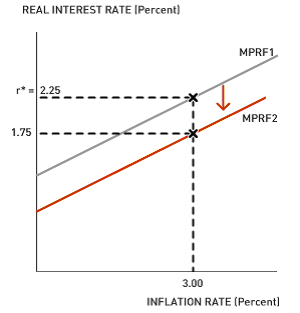

Of course, the MPRF above is just one example, and there are other examples (such as the  The graph shows that a downward shift in the MPRF reduces the actual real interest rate from 2.25% to 1.75% when the actual inflation rate is equal to the initial target inflation rate of 3%. Assuming that the actual inflation rate remains constant in the short run, the shift in the MPRF causes a reduction in the real interest rate, and consequently stimulates investment and consumption. The ultimate goal is to stimulate aggregate demand and prevent the recent financial turmoil from drastically affecting the broader economy.

The graph shows that a downward shift in the MPRF reduces the actual real interest rate from 2.25% to 1.75% when the actual inflation rate is equal to the initial target inflation rate of 3%. Assuming that the actual inflation rate remains constant in the short run, the shift in the MPRF causes a reduction in the real interest rate, and consequently stimulates investment and consumption. The ultimate goal is to stimulate aggregate demand and prevent the recent financial turmoil from drastically affecting the broader economy. The Federal Open Market Committee (

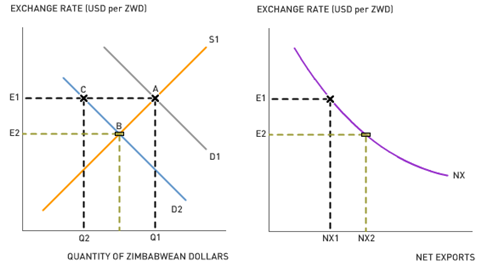

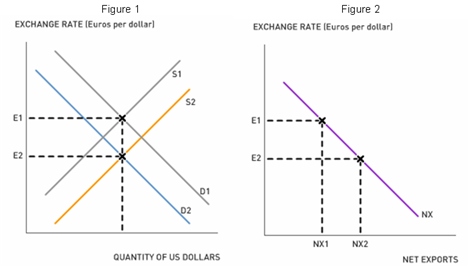

The Federal Open Market Committee ( A depreciation of the U.S. currency will make U.S. exports relatively inexpensive for foreigners while making imports from foreign countries relatively expensive for Americans. A decrease in the interest rate causes an increase in net exports and reduces the size of the U.S. trade deficit. Figure 2 shows the relationship between the exchange rate and net exports. Since net exports are a component of total spending in the U.S. economy, the Fed's rate cut provides two boosts to aggregate spending: (1) the rate cut stimulates consumption and investment because the cost of borrowing decreases; and (2) the rate cut stimulates net exports due to U.S. dollar depreciation. By cutting the target fed funds rate, the Fed intends to prop up spending and growth at a time when tightening credit conditions threaten to slow or reverse the growth of economic output.

A depreciation of the U.S. currency will make U.S. exports relatively inexpensive for foreigners while making imports from foreign countries relatively expensive for Americans. A decrease in the interest rate causes an increase in net exports and reduces the size of the U.S. trade deficit. Figure 2 shows the relationship between the exchange rate and net exports. Since net exports are a component of total spending in the U.S. economy, the Fed's rate cut provides two boosts to aggregate spending: (1) the rate cut stimulates consumption and investment because the cost of borrowing decreases; and (2) the rate cut stimulates net exports due to U.S. dollar depreciation. By cutting the target fed funds rate, the Fed intends to prop up spending and growth at a time when tightening credit conditions threaten to slow or reverse the growth of economic output. As

As