Inflation Gone Wild

by William Chiu With an annual inflation rate of 1,600%, Zimbabwe currently holds the world title for fastest-increasing prices. As the late Milton Friedman put it, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon. To control inflation, you need to control the money supply.” The inflation cure seems simple to understand from a textbook perspective: drastically cut back the money supply in order to lower the expected inflation rate.

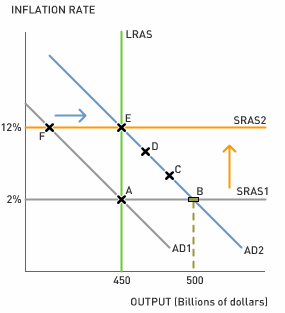

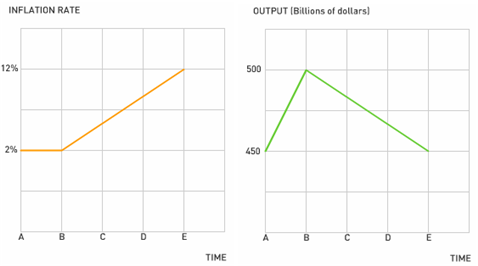

With an annual inflation rate of 1,600%, Zimbabwe currently holds the world title for fastest-increasing prices. As the late Milton Friedman put it, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon. To control inflation, you need to control the money supply.” The inflation cure seems simple to understand from a textbook perspective: drastically cut back the money supply in order to lower the expected inflation rate.Unfortunately, the cure might be worse than the disease. With the current unemployment rate at 80%, drastic cuts in the money supply could increase unemployment and cause a coup d'état before the expected inflation rate falls. The monetary contraction is inevitable if Zimbabwe wishes to tame the inflation monster, and the International Monetary Fund has urged the government to liberalize its exchange rate regime as a means to cushion the unemployment effects.

In order to understand the IMF’s position on Zimbabwe’s exchange rate, we must examine how maintaining an overvalued currency might contribute to soaring inflation, and how floating the currency might provide relief to both inflation and unemployment.

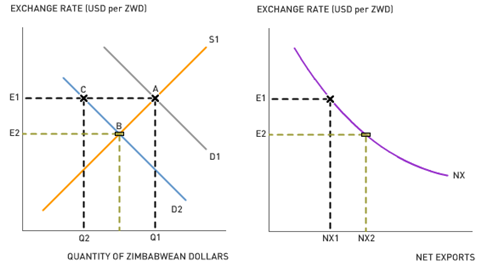

The graph on the left shows the market for Zimbabwean dollars. Assume that the government fixes the exchange rate at E1. A fixed exchange rate is the official value of the currency despite fluctuations in supply and demand. Initially, the official value equals the market value where D1 intersects S1 (point A). Then, due to unsustainable fiscal deficits and government land reforms that usurp private property, foreign investors flee Zimbabwe. Consequently, the demand for Zimbabwean dollars decreases from D1 to D2.

If Zimbabwe were under a floating exchange rate regime, the fall in demand for Zimbabwean dollars would result in the depreciation of the currency from E1 to E2 (point B). But because Zimbabwe’s government insists on a fixed exchange rate regime, the fall in demand for Zimbabwean dollars will cause a surplus of Zimbabwean dollars (Q1 - Q2). At point C, the currency is considered overvalued because the official value is greater than the market value. In order to eliminate downward pressures on the currency, Zimbabwe will instruct its central bank to buy the surplus of Zimbabwean dollars (and sell U.S. dollars), which will return the market to point A. Zimbabwe's central bank will eventually deplete its U.S. dollar reserves as the economy deteriorates from questionable domestic policies, and will borrow U.S. dollars in order to maintain the fixed exchange rate.

If Zimbabwe were under a floating exchange rate regime, the fall in demand for Zimbabwean dollars would result in the depreciation of the currency from E1 to E2 (point B). But because Zimbabwe’s government insists on a fixed exchange rate regime, the fall in demand for Zimbabwean dollars will cause a surplus of Zimbabwean dollars (Q1 - Q2). At point C, the currency is considered overvalued because the official value is greater than the market value. In order to eliminate downward pressures on the currency, Zimbabwe will instruct its central bank to buy the surplus of Zimbabwean dollars (and sell U.S. dollars), which will return the market to point A. Zimbabwe's central bank will eventually deplete its U.S. dollar reserves as the economy deteriorates from questionable domestic policies, and will borrow U.S. dollars in order to maintain the fixed exchange rate.Since the loans are denominated in U.S. dollars, Zimbabwe must make periodic payments in U.S. dollars or face getting cut off from all sources of international capital. Due to disastrous domestic policies, the government has little tax revenue to make those periodic payments, and the only way to service their international debts is to print more money, just as Germany did after World War I. As the central bank expands the money supply to pay international debts, inflation increases, which places additional downward pressure on the Zimbabwean dollar: as foreigners demand less and less of the failing currency, Zimbabwe has to print more and more money, and sooner or later, everything will spin out of control.

One solution is to eliminate the fixed exchange rate regime altogether and allow the Zimbabwean dollar to float freely. If the currency were allowed to float today, its value would fall tremendously, which would stimulate exports and reduce imports. The graph on the right shows that as the exchange rate falls from E1 to E2, net exports increase from NX1 to NX2. A floating exchange rate would boost job creation as the central bank institutes the tough medicine of curing inflation by drastically reducing the money supply.

Discussion Questions

1. If the fixed exchange rate regime were eliminated, what would happen to the size of Zimbabwe's international debts in terms of Zimbabwean dollars? Would it increase or decrease?

2. The central bank has recently declared inflation illegal. How do price controls affect domestic markets like those for corn, wheat, electricity, and labor?

3. This analysis assumes that Zimbabwe's reduction in real GDP is due to domestic policies such as unsustainable fiscal deficits and poor private property rights. How might hyperinflation directly contribute to higher unemployment?

Labels: Exchange Rate, Expectations, Inflation, International Economics, Monetary Policy, Quantity Theory of Money, Trade Deficit