The Opportunity Costs of Relationships

by Chrissie Deist Since it is generally easy to compare the price-tag cost of one good or service against another, people tend to consider only the monetary cost of a decision. However, what’s also important to consider is the whole value of what you are giving up when you make a decision. In economics, this is known as the opportunity cost. A simple textbook example describes a market that offers two goods for sale: apples and oranges. If an apple can be bought for $1 and an orange for $0.50, the monetary cost of buying an apple is $1, but the opportunity cost is equal to how much you value the two oranges that you give up if you choose to buy an apple. While this observation may not seem particularly important in this context, it can be applied far beyond the realm of monetary dealings.

Since it is generally easy to compare the price-tag cost of one good or service against another, people tend to consider only the monetary cost of a decision. However, what’s also important to consider is the whole value of what you are giving up when you make a decision. In economics, this is known as the opportunity cost. A simple textbook example describes a market that offers two goods for sale: apples and oranges. If an apple can be bought for $1 and an orange for $0.50, the monetary cost of buying an apple is $1, but the opportunity cost is equal to how much you value the two oranges that you give up if you choose to buy an apple. While this observation may not seem particularly important in this context, it can be applied far beyond the realm of monetary dealings.Romantic relationships are obviously not regular commodities like apples and oranges in that you don’t just head to your local date market and buy a girlfriend or boyfriend. Despite this violation of the competitive hypothesis, relationships have opportunity costs too. That is, the opportunity cost of a relationship is comprised of all the things one foregoes to be in that relationship. While it is not difficult to see the many wonderful things you gain from having a romantic partner, it is easy to overlook the things you give up in exchange.

Here’s a list of some of the things that most people forgo to some degree to be in a relationship:

(1) Spending time with friends and family

(2) Going out and meeting new people

(3) Developing or engaging in hobbies

(4) Working

(5) Exercising

Some people may find that being in a relationship allows them to do more of some of these things (maybe you work out together or spend lots of time with mutual friends), but usually the time you spend with your significant other tends to edge out at least some of the things you like to do on your own.

In economics we represent such trade-offs using graphs like the one below. The red line is known as the budget constraint, and while it typically represents a monetary budget, in this case it represents a sort of time budget for an individual in a relationship with eight hours of leisure time per day (assuming eight hours of sleep and eight hours of work). The eight hours of leisure can be divided anywhere between spending all 8 hours with your significant other or all 8 hours doing other things. Regardless of what allocation a person chooses on the red line, any movement along the line represents a tradeoff of one activity for another.

Despite the perception of economics as dismal science, the point is not that the cost of relationships outweighs the benefits, but rather that there is an opportunity cost to everything. So if you’re single and accustomed to thinking about all the things you’re missing out on, take comfort in the things that you aren't giving up.

Discussion Questions:

1. Consider the graph depicting the time-budget constraint. If a person quits their job and suddenly has more time, how does this affect the person’s position on the line or the position of the line itself?

2. If person A and person B primarily give up time spent with friends when they are in relationships, and person B really likes being with friends, which person’s relationship comes at a higher opportunity cost? If you were to draw each of their indifference curves on the budget constraint graph, how would the two compare?

3. How would being in a relationship affect your overall consumption? If you are in a relationship, are there some goods or services that you would consume more or less of in a given week? Which of these goods would you say are “complementary goods” with relationships? Which are “substitutes?”

4. Sometimes when economists model consumption choices for goods that are consumed over longer periods of time, they introduce switching costs. What sorts of things associated with a break-up may be considered a switching cost? If you assume that breakups are costly, how might this change a person’s decision to allocate their time?

Labels: Cost-Benefit Analysis, Opportunity Cost, Tradeoffs

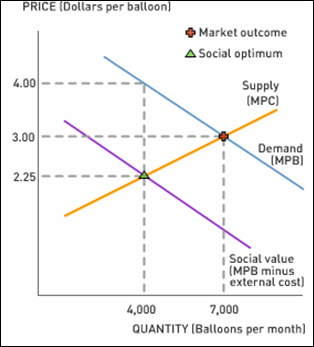

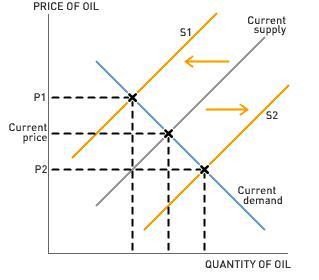

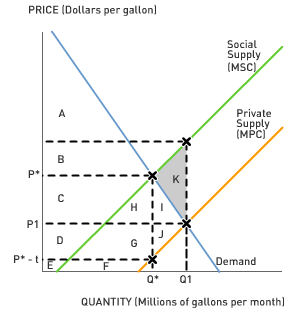

As a recurring Winter Olympics viewer, I am counting down the days until the games begin on February 12. As an economist, however, I am intrigued by the number of tools an introductory economics course provides students with to analyze the effects of the Olympic games on the local economy of Vancouver. Three topics in particular come to mind that most students will encounter in a basic economics course: consumer spending, negative externalities, and cost-benefit analysis.

As a recurring Winter Olympics viewer, I am counting down the days until the games begin on February 12. As an economist, however, I am intrigued by the number of tools an introductory economics course provides students with to analyze the effects of the Olympic games on the local economy of Vancouver. Three topics in particular come to mind that most students will encounter in a basic economics course: consumer spending, negative externalities, and cost-benefit analysis.

I love Radiohead. Really, love. I still remember sitting in my car in the record store parking lot with one of my best friends, listening to their fourth record,

I love Radiohead. Really, love. I still remember sitting in my car in the record store parking lot with one of my best friends, listening to their fourth record,

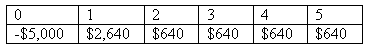

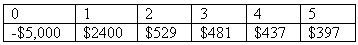

When is a bad idea a good idea? Consider "loss leaders," where stores sell products below cost to lure consumers in to buy the sale item and then get them to purchase other stuff on which there is a higher profit margin. How about free cell phones when you sign a service contract?

When is a bad idea a good idea? Consider "loss leaders," where stores sell products below cost to lure consumers in to buy the sale item and then get them to purchase other stuff on which there is a higher profit margin. How about free cell phones when you sign a service contract?