Should the Government Bail Out the Auto Industry?

by Victoria Miu America's Big Three—General Motors, Chrysler, and Ford—are in big trouble. Sales from the not-so-fuel-efficient fleet of American-made vehicles had already suffered considerably because of high gas prices even before the financial crisis began to get serious in September of 2008. Faced with undesirable terms in private credit markets, the Big Three are now turning to the government for financial assistance. The House passed a bill to rescue the Big Three car companies with $15 billion in emergency loans on Wednesday, December 10, but the Senate abandoned the plan the day after. Should the government bail out the auto industry?

America's Big Three—General Motors, Chrysler, and Ford—are in big trouble. Sales from the not-so-fuel-efficient fleet of American-made vehicles had already suffered considerably because of high gas prices even before the financial crisis began to get serious in September of 2008. Faced with undesirable terms in private credit markets, the Big Three are now turning to the government for financial assistance. The House passed a bill to rescue the Big Three car companies with $15 billion in emergency loans on Wednesday, December 10, but the Senate abandoned the plan the day after. Should the government bail out the auto industry?Those in favor of the bill argued that the rescue plan can prevent the loss of 500,000 jobs in the auto industry. Job losses in the auto sector would most likely have spillover effects in other sectors. As auto workers lose their jobs, they would consume fewer goods and services, negatively affecting industries in retail, health care, and financial services. With unemployment already rising, supporters of the bailout argued that keeping auto workers in their jobs is much easier than creating new jobs for them.

Opponents of the bill compared the bailout to the inefficiencies generated by government subsidies and tariffs. Many companies face financial problems—why should the government save the Big Three and not the others? Poor performance is typically a good signal that a company should change how and what it produces. A partial government takeover of American auto companies will not ensure that the firms will start producing vehicles that people want to buy. A bailout, according to critics, will simply prolong the inevitable: the consolidation of the American auto industry, the large number of layoffs that come with it, and the migration of workers from autos to more profitable industries.

Discussion Questions

1. What is the role of labor unions in contributing to the financial problems facing the Big Three? In particular, how well do the wages reflect the productivity of the workers in the Big Three? Click here to read more.

2. Do you think the problems faced by the Big Three stem primarily from the recent financial crisis or from longer-term decisions about what types of vehicles to produce and how to produce them?

3. Some suggest that another reason leading to the failure of the Big Three is that American consumers prefer cars made by foreign companies, such as Toyota and Honda, to cars made by American-owned companies. How does the market of foreign-made cars affect the demand for American cars?

4. Foreign-owned automakers, like Toyota and Honda, operate production facilities in the United States and employ American workers. How would these firms be affected by a bailout of the American-owned Big Three? How will foreign auto firms with operations in and outside of the United States be affected if one or more members of the Big Three were allowed to fail?

5. How do the loans compare with tariffs in foreign trade? What advantages and disadvantages do they share in common?

6. What would happen to the broader economy if the plants closed and workers became laid off? What might these workers do to find new employment? Which sectors would employ them?

Labels: Business Cycle, Global Economic Watch, Government, Labor, Unemployment

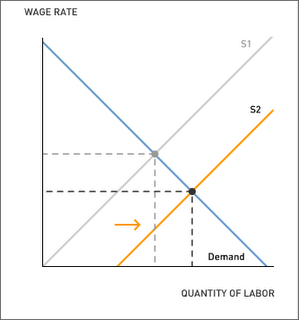

So what are the sources of the farm labor shortages in the U.S. and Britain?

So what are the sources of the farm labor shortages in the U.S. and Britain?