Recent Land Reform in China

by Victoria Miu The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) collectivized—or assigned ownership to a collective rather than to individuals—all land in 1950s. In a second round of land reforms 30 years ago, the CCP assigned small plots of land to each rural family. Families could use the land as they saw fit and sell the resulting crops but the state maintained ownership of the land itself. Selling the property was therefore out of the question.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) collectivized—or assigned ownership to a collective rather than to individuals—all land in 1950s. In a second round of land reforms 30 years ago, the CCP assigned small plots of land to each rural family. Families could use the land as they saw fit and sell the resulting crops but the state maintained ownership of the land itself. Selling the property was therefore out of the question.Last week, the CCP announced a third round of land reforms, allowing farmers to "subcontract, lease, exchange or swap" their land-use rights. Although farmers cannot sell their land, they can lease their land to other farmers for up to 70 years in exchange for cash. For China, the reform represents another step away from communism and another step toward a market-based economy.

Proponents of the policy hope for four positive effects. First, exchange of land among farmers should lead to a more efficient allocation of resources. Previously, people who wanted to leave the farm for work in the cities left their plots of land in the care of elderly parents. Under the new policy, those people can subcontract their land-use rights to farmers who place a higher value on the rights to use the land.

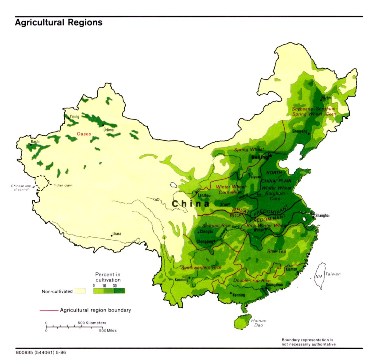

Second, the reform should allow farmers to enjoy economies of scale—the cost reductions that result from higher levels of output. Before the reform, each rural family had a small plot of land, limiting the use of machinery and technology in farming. As a result, agriculture in China remains labor-intensive. The exchange of land-use rights will allow the development of more commercial-scale, larger farms, where farmers can take advantage of more advanced agricultural technology. As farming yields rise, so will China's total contribution to the world food supply.

Higher yields may contribute to the third potential benefit: higher incomes for families in the Chinese countryside. The incomes of some farmers will rise along with the output per acre. Those who would rather leave the countryside can now cash in their land-use rights and pursue better paying opportunities in the cities. The rising incomes should lower the income gap between rural and urban households, easing a social tension.

Finally, the new policy should provide more property protection to farmers. Before, without the rights to lease state-owned land, land grabs by local authorities left many rural families with little to nil in the way of compensation.

Of course, there is no guarantee that the policy will work as intended. Opponents of the measure worry about the effects of the reforms. They argue that the policy will force some farmers to lease property and join the ranks of cheap labor in the cities, increasing the income gap even more as land-use rights become concentrated in the hands of well-off farmers.

Discussion Questions

1. Do you believe that the new policy would provide adequate property protection for small farmers? Could land grabs still occur? Why or why not? Can you think of other economic or political challenges the reforms will create?

2. What new pressures will the cities face if many farmers lease their land and move to urban areas?

3. The ongoing financial crisis in developed countries overshadows the ongoing food crisis in developing countries. The food crisis refers to rising prices for basic food like rice and wheat. If China's land reforms work as intended, how might they affect the global food crisis?

Labels: China, Efficiency, Gains from Trade, Income Inequality, Productivity