Towards Gasoline Market Efficiency

by Michael Enriquez

For the past year or so, I’ve been using the same website to save money on gasoline. The parent site of the one I use is Gas Buddy. Commuting to work I spend about $130 per month on gas, or roughly $1,550 per year. There are several reasons for this. Gasoline is one of my biggest work-related expenses, California gas prices are consistently among the highest in the nation, and I’m also an economist. I feel impelled to fill up at the station offering gasoline at the cheapest price, without going significantly out of my way to get there, of course.

Economic theory would typically classify a local gasoline market as a competitive market, yet, I often see differences of 20-25¢ per gallon for the same gasoline grade among nearby stations. Why does the standard model of competition not seem to apply here? Because most consumers probably accept the notion that gasoline of the same grade is nearly identical regardless of the station, competition should drive prices to the same competitive market clearing price. However, gasoline retailers often try to differentiate their product through methods such as affiliated credit cards, which give the holders a discount when they purchase gas with the card from a retailer that is part of the corporate chain. Another strategy they use is to offer a discount on a car wash to consumers who have purchased gas at their station. Nevertheless, it doesn’t seem like such differentiation would be important enough to keep the market from a perfectly competitive equilibrium.

What else might explain these facts? One possibility is that some gas stations employ a strategy of luring customers into their stores with gasoline sold below cost, to sell them high margin convenience goods. Another possibility is that some stations enjoy location advantages that allow them to command higher prices, such as the first station located off of a high traffic freeway exit. Nevertheless, the explanation that I prefer is that gasoline consumers do not have all of the information regarding prices of gasoline in surrounding areas. Websites like Gas Buddy help alleviate this informational deficiency in a nearly costless way thanks to its gas price maps and price lists. As more people use the site, the local gasoline markets covered should theoretically approach a perfectly competitive equilibrium.

Where does the website get its price information? People who are interested in either winning gas cards or making the gas market more efficient have accounts on the site and post gas prices there. Although there are obvious benefits to the information provided by Gas Buddy, there may also be drawbacks to the site. Besides the obvious damage to the profits of gas station companies, there are likely to be people who misuse the information. For example, imagine the user who drives several miles out of his way to fill-up on gas that is only 5 cents cheaper per gallon than the nearest station. This person may save $.75 or so, but environmental costs of the extra driving distance, the cost of the additional gasoline used and vehicle wear, and the value of the person’s extra driving time are likely to sum to significantly more than $.75. So, while getting the cheapest gas is great, remember that there are more to costs than just retail prices.

Author’s note 10/19/09: During her review of this post, Kasie Jean mentioned the possibility that consumers may have gasoline brand loyalties. The author found this unlikely but later received advice from a trusted mechanic regarding the benefits of Chevron with Techron gasoline. The author owns no securities issued by the Chevron corporation.

Discussion Questions

1. Now that you are aware of a gasoline price website, would you use one to locate the cheapest nearby gas prices? Why or why not?

2. Think about the characteristics of perfectly competitive markets. Do you believe that gasoline markets are perfectly competitive? If not, what are some aspects, besides those described above, that keep them from perfect competition?

3. In 2007, a study concluded that the optimal tax on gasoline was $2.10 per gallon. What is your opinion of this conclusion? Do you think that gas price websites would be viewed more if gasoline taxes were significantly higher?

4. In what other ways has the internet made markets more efficient or perhaps less efficient?

Labels: Economics of Search, Efficiency, Gas Tax, Perfect Competition

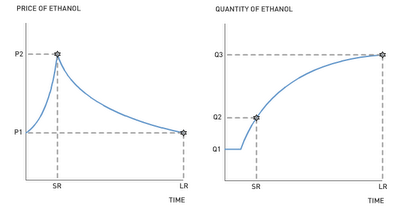

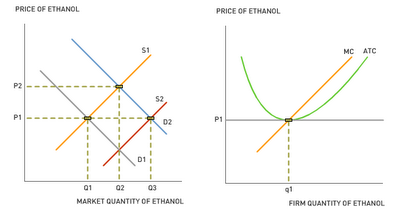

Notice that economic profits converge to zero in the long run. As explained by most textbooks, zero economic profit does not mean that ethanol producers barely have enough to eat. Zero economic profit means that ethanol producers are earning incomes that compensate them for the next best salary they had to give up to go into producing ethanol.

Notice that economic profits converge to zero in the long run. As explained by most textbooks, zero economic profit does not mean that ethanol producers barely have enough to eat. Zero economic profit means that ethanol producers are earning incomes that compensate them for the next best salary they had to give up to go into producing ethanol.