Why Do Monthly Job Loss Estimates Exclude the Farming Sector?

by Brandon Fuller In April, nonfarm payroll employment declined by more than 500,000 jobs for the sixth month in a row. While the pace of nonfarm job losses slowed, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) report on the employment situation continues to paint a fairly grim picture. Employment in the farming sector was actually a bit higher in January 2009 (the most recent month for which data is available) than it was in January 2008. Why doesn't the BLS cover farms and ranches in its payroll survey? Might the omission of the farming sector from the BLS payroll survey cause the jobs report to be too gloomy?

In April, nonfarm payroll employment declined by more than 500,000 jobs for the sixth month in a row. While the pace of nonfarm job losses slowed, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) report on the employment situation continues to paint a fairly grim picture. Employment in the farming sector was actually a bit higher in January 2009 (the most recent month for which data is available) than it was in January 2008. Why doesn't the BLS cover farms and ranches in its payroll survey? Might the omission of the farming sector from the BLS payroll survey cause the jobs report to be too gloomy?According to the BLS, farms simply fall outside the scope of the payroll survey. When the BLS began studying payrolls and employment in 1915, it focused exclusively on the manufacturing sector. The need for more accurate employment estimates during the Great Depression led the BLS to develop more comprehensive estimates of wages and employment in nonfarm industries during the '30s. Historically, at least, one can imagine the relative difficulty of gathering timely employment information in the rural farming sector.

The lack of agriculture in the payroll survey, however, is almost certainly inconsequential. The absence of farms in the Bureau's payroll survey matters less to today's employment picture than it did during the early and mid 20th century. In 1930, 21.5 percent of the workforce worked in farming, and agricultural output represented nearly 8 percent of U.S. economic output. At the turn of the 21st century, less than 2 percent of the labor force worked in agriculture, a sector that now represents less than 1 percent of national economic output.

The small share of the population employed in agriculture makes it unlikely that the Bureau's payroll survey--with a sample covering about one-third of total nonfarm payroll employment--will distort the overall jobs picture by failing to account for farm sector employment. Even an agricultural boom in the midst of the current recession would do little to reverse the dismal national employment trends.

Although the BLS excludes agriculture from its payroll survey, it does capture farm employment indirectly through a survey of 60,000 households. The most widely reported unemployment rate comes from this household survey, which includes respondents from all economic sectors: manufacturing, services, agriculture, or the ranks of the self-employed.

The household survey categorizes a person as employed if they worked for pay at some point during the past week, whether she worked in a factory, on a ranch, in an office, or for herself. A person who does not have a job, but actively searched for one at some point in the preceding four weeks, is considered unemployed. Anyone who does not have a job and has not been looking in the past month is classified as "not in the labor force."

The unemployment rate is simply the ratio of unemployed workers to the labor force (the sum of employed and unemployed workers). As the ranks of the unemployed continued to swell during April, the unemployment rate rose from 8.5 percent to 8.9 percent, reflecting an increase in joblessness among all workers, including farm hands and the self-employed.

Discussion Questions

1. There are a number of jobless people who would like to work but have given up on their job search because they believe it to be futile. The BLS classifies these discouraged workers as 'not in the labor force' rather than unemployed because they did not search for a job in the preceding four weeks. Consulting this table, how does the number of discouraged workers in April 2009 compare to the number in April 2008? If the BLS were to count discouraged workers as unemployed (and, by extension, part of the labor force), what would happen to the unemployment rate?

2. How has the recession affected the ranks of discouraged workers? For more information, consult this recent BLS report.

3. The BLS tracks the number of people who work part time for economic reasons, also known as involuntary part-time workers. By counting anyone who worked for pay during the preceding week as employed, the household survey classifies a number of involuntary part-time workers as employed. In what way does the official unemployment rate miss the underemployment associated with involuntary part-time work? This table contains information on involuntary part-time workers. How has the recession impacted the number of people employed part-time for economic reasons? What happened to the number of involuntary part-time workers between March 2009 and April 2009?

4. Even as Americans eat a larger variety and quantity of foods than ever before, the share of economic output attributable to agriculture declines. How can you explain this development?

Labels: Economic Growth, Global Economic Watch, Unemployment

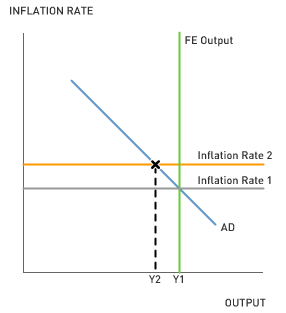

is the inflation rate:

is the inflation rate:

For many people, the pain of losing $500 outweighs the pleasure of gaining $500. As Austan Goolsbee points out in a recent

For many people, the pain of losing $500 outweighs the pleasure of gaining $500. As Austan Goolsbee points out in a recent

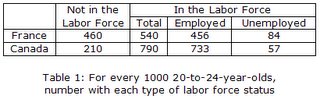

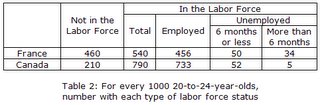

Yet other statistics show more clearly that the labor market opportunities for some young people in France are in fact much worse than in Canada. One useful measure is the duration of unemployment. For each 1000 young people in France, take the 84 who are in the labor force and unemployed. Of these, 34 have been unemployed for more than 6 months. Of the corresponding 57 people who are unemployed in Canada, only 5 have been unemployed for this long. (See Table 2, below.) This tells you that on average, spells of unemployment last much longer in France.

Yet other statistics show more clearly that the labor market opportunities for some young people in France are in fact much worse than in Canada. One useful measure is the duration of unemployment. For each 1000 young people in France, take the 84 who are in the labor force and unemployed. Of these, 34 have been unemployed for more than 6 months. Of the corresponding 57 people who are unemployed in Canada, only 5 have been unemployed for this long. (See Table 2, below.) This tells you that on average, spells of unemployment last much longer in France. So the two major differences between France and Canada are (1) France has a lower labor force participation rate, and (2) long-term unemployment is much more prevalent in France. There are several explanations for these differences. A recent article in the Financial Times suggested that the main reason for the lower labor force participation rate may be that more twenty-somethings in France attend university. In fact, this can account for only a small part of the difference. The fraction of 20- to- 24-year-olds in education is only five percentage points higher in France--44% compared with 39% in Canada. Most of the 25 percentage point difference in labor force participation rates must therefore arise for some other reason.

So the two major differences between France and Canada are (1) France has a lower labor force participation rate, and (2) long-term unemployment is much more prevalent in France. There are several explanations for these differences. A recent article in the Financial Times suggested that the main reason for the lower labor force participation rate may be that more twenty-somethings in France attend university. In fact, this can account for only a small part of the difference. The fraction of 20- to- 24-year-olds in education is only five percentage points higher in France--44% compared with 39% in Canada. Most of the 25 percentage point difference in labor force participation rates must therefore arise for some other reason.