Bovine Intervention

by Brandon Fuller

Why tax livestock? In a word, flatulence. (In two, enteric fermentation.) Cows belch and otherwise discharge their way to about 14% of the world's methane emissions. Like carbon dioxide, methane is a greenhouse gas. Although methane accounts for a relatively small share of all greenhouse gas emissions, it is alarmingly effective at preventing heat from escaping the planet. Compared to carbon dioxide, a little bit of methane goes a long way toward raising the potential for climate change. Reducing methane emissions would help Denmark and Ireland meet their EU climate policy commitments.

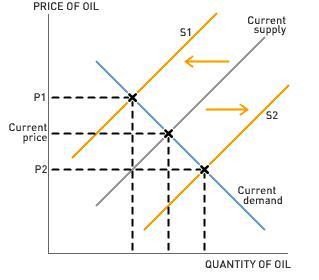

Raising livestock generates a negative externality: the costs of methane emissions are born by the general public rather than those directly involved in the production and consumption of meat and dairy. The emissions cause the marginal social cost of producing a pound of beef to exceed the marginal private cost.

The proposed taxes are an attempt to force farmers and ranchers to internalize the heretofore external costs of the methane emissions, bringing the private costs of raising livestock closer inline with the social costs. The tax would raise the costs of producing meat and dairy, reduce the supply of such products, and, consequently, lower methane emissions.

While a tax based on the number of cattle in a herd would undoubtedly reduce farming-related green house gas emissions, it would do so in rather blunt fashion. To see why, consider two ranchers. The first uses specialized cattle feed to reduce the methane emissions of his herd. The second sticks to traditional methods with the typically methane-intensive results. The cow tax, however, is levied equally on each head of cattle, failing to account for the methane reduction efforts of the first rancher.

While the cow tax provides an incentive to cut back on cattle, it doesn't encourage ranchers to adopt any of the promising technologies devised to reduce methane discharge from individual cows. Ideally, climate change policies should focus on the amount of methane emitted rather than the number of cows.

Discussion Questions

1. Can you think of policies to incentivize the adoption of methane-reducing technologies in farming and ranching?

2. Governments in Europe and the United States heavily subsidize the farming and ranching sectors of their economies. How would the removal of such subsidies impact methane emissions in Europe and the U.S.? What about methane emissions from less developed countries?

Labels: Efficiency, Environment, Externalities, Incentives, Taxes

In an important scene from the 1999 movie American Beauty, two characters—Jane and Ricky—watch

In an important scene from the 1999 movie American Beauty, two characters—Jane and Ricky—watch