Pigouvian Tax the Rich?

by Derek Gurney A millionaire in Switzerland was recently fined a world-record $290,000 for driving his Ferrari Testarossa 87 miles per hour in a 50 miles per hour zone. The amount was so high because fines for speeding in Switzerland are based on a driver's wealth (and, in this case, because the driver falsely claimed diplomatic immunity). The story got me thinking about the economics of speeding tickets.

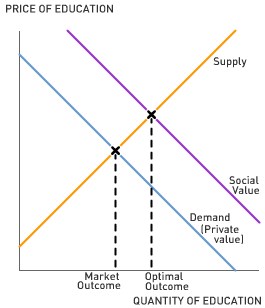

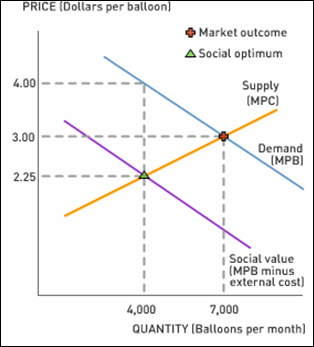

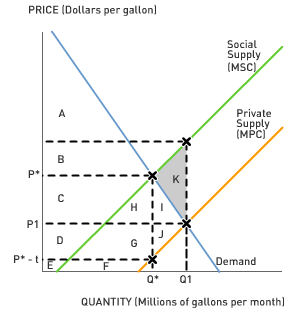

A millionaire in Switzerland was recently fined a world-record $290,000 for driving his Ferrari Testarossa 87 miles per hour in a 50 miles per hour zone. The amount was so high because fines for speeding in Switzerland are based on a driver's wealth (and, in this case, because the driver falsely claimed diplomatic immunity). The story got me thinking about the economics of speeding tickets.To an economist, speeding tickets can potentially act as a Pigouvian tax: a tax that makes an individual's cost of engaging in an activity equal to the cost imposed on society. For a driver, the cost of speeding includes things like fuel, the increased likelihood of damaging one's car, and injuring oneself in an accident. For society as a whole, though, the cost of speeding also includes the increased likelihood of an accident that damages other people's property or injures other people. As a result, speeding (and driving in general) imposes costs on society above and beyond those incurred by the driver. Moreover, the other people affected by speeding aren't compensated for the risk by the benefits of speeding, which are enjoyed strictly by the driver. Economists refer to the costs from an activity that are imposed on other people without any compensation as negative externalities. By making an individual's costs equal to society's costs, a Pigouvian tax gives individuals incentives to act as if they were considering everyone's costs. By doing so, a Pigouvian tax internalizes the externality and decreases the activity to the level that maximizes net benefits to society.

It can be difficult to set the Pigouvian tax exactly equal to the external costs of driving because these depend on so many hard-to-estimate variables (such as the likelihood of accidents at different speeds and the monetary damage caused by injuries or death). It's easy to determine, however, that externalities don't depend on the wealth of the driver. For example, the potential consequences for others of a poor person driving a rented Ferrari at 87 miles per hour are the same as from a rich person driving his own Ferrari at the same speed. Thus, for speeding tickets to serve as a Pigouvian tax, the fine for driving the same speed in the same car in the same conditions should be the same for everyone, regardless of wealth.

One consequence of not basing them on wealth, however, is that wealthier people will likely speed more. In most cases, the richer you are, the more you are willing to spend to save time, and thus the more willing you are to speed and risk getting a ticket. Moreover, if the "pure desire for speed" (in the words of the Swiss court that sentenced the driver) is a normal good, wealthier people will consume more of it. From an efficiency perspective, this result is completely appropriate. As long as individuals act as if they were considering all the costs of an activity, their decision to engage in it means that there are net benefits to them and thus to society.

However, because speeding puts others' lives at risk, the idea that it is appropriate for wealthier people to speed more runs counter to many people's idea of fairness. Switzerland's law suggests that its citizens are willing to forego the efficient level of speeding in order to obtain an arguably more equitable result—everyone has similar incentives to speed, and endanger others, regardless of wealth. So, if you ever find yourself about to drive in Switzerland, be sure to check your bank account first: the less you have, the better.

Discussion Questions:

1. What if, considering its external costs, $290,000 was actually the appropriate fine for speeding, but that only extremely wealthy drivers paid that much, with most drivers paying considerably less. Who would speed at the appropriate rate, while who would speed more than was appropriate?

2. Consider what factors make speeding more or less dangerous for other people. On what variables could you base fines for speeding so that drivers internalized the external costs?

3. Are there variables used to determine fines for speeding where you live that have little or no relation to the external costs of speeding?

4. In addition to acting as a deterrent for speeding, fines for speeding can also serve as a source of government revenue. How does this consideration impact the efficiency and equity of basing the fines on wealth?

Labels: Externalities, Pigouvian Taxes, Speeding Tickets, Wealth

As a recurring Winter Olympics viewer, I am counting down the days until the games begin on February 12. As an economist, however, I am intrigued by the number of tools an introductory economics course provides students with to analyze the effects of the Olympic games on the local economy of Vancouver. Three topics in particular come to mind that most students will encounter in a basic economics course: consumer spending, negative externalities, and cost-benefit analysis.

As a recurring Winter Olympics viewer, I am counting down the days until the games begin on February 12. As an economist, however, I am intrigued by the number of tools an introductory economics course provides students with to analyze the effects of the Olympic games on the local economy of Vancouver. Three topics in particular come to mind that most students will encounter in a basic economics course: consumer spending, negative externalities, and cost-benefit analysis. With significant contributions and analysis from Kasie R. Jean.

With significant contributions and analysis from Kasie R. Jean.

In an important scene from the 1999 movie American Beauty, two characters—Jane and Ricky—watch

In an important scene from the 1999 movie American Beauty, two characters—Jane and Ricky—watch

It’s 85 degrees and sunny on this October day in the Bay Area, and this morning’s review of the

It’s 85 degrees and sunny on this October day in the Bay Area, and this morning’s review of the

When is a bad idea a good idea? Consider "loss leaders," where stores sell products below cost to lure consumers in to buy the sale item and then get them to purchase other stuff on which there is a higher profit margin. How about free cell phones when you sign a service contract?

When is a bad idea a good idea? Consider "loss leaders," where stores sell products below cost to lure consumers in to buy the sale item and then get them to purchase other stuff on which there is a higher profit margin. How about free cell phones when you sign a service contract?