Proposition 87, a hotly contested measure on the ballot in California, nicely illustrates the key lessons about tax incidence--who actually pays a tax. The political debate about this Proposition shows that these lessons, which are typically covered in an introductory microeconomics course, are not well understood by the voting public. Is education powerful or what? Armed with knowledge of just a few economic principles, you will be able to analyze important policy issues better than most.

To raise funds for research on and development of alternative fuels, Proposition 87 taxes oil produced in California. (Read a

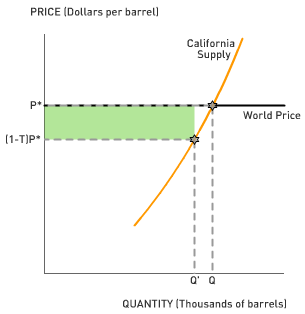

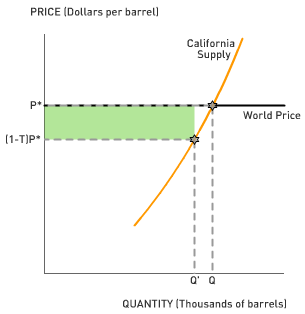

summary of the provisions of this act on the Secretary of State's web site.) Opponents of the tax claim that this tax will increase the price of gasoline at the pump. The following figure shows why this claim is wrong. The market for oil is global, and the price of oil is set by global supply and global demand. California produces less than 1% of all the oil produced in the world, so changes of a few percent in its output would be far too small to have a noticeable effect on global supply and demand. Taken together, all the producers in California are in the same position as a single firm in a competitive industry. They face a residual demand curve for their oil that is horizontal, or perfectly elastic, at a price equal to the world price of oil plus the cost of transporting it to California. Call this price P*.

To understand why the demand curve faced by local producers is horizontal, consider the decisions made by the typical manager of a gasoline refinery. She already has barrels of imported oil delivered to her at the price P* and could order many more at that same price. If the price of oil delivered from a local producer was more than P*, she wouldn't buy any. If it was less, she'd buy as much as she could and cut back on purchases of oil brought into the state from Alaska and the rest of the world. Local producers, understanding this, would be foolish to charge a price less than P*. They'd be leaving money on the table. Even if they did, this wouldn't reduce the price that the refinery manager would charge for gasoline. She'd happily buy all the cheap local oil she could, but still charge the same price for gasoline that other refiners, who continue to import foreign oil, are charging--the price determined by P* and the cost of refining.

What happens if the state of California imposes a tax of T% on the oil produced by the local producers? The figure shows that the price of oil purchased by the refineries is still equal to P*. Local producers receive (1 - T) times P* per barrel of oil. Because they face a horizontal demand curve, they bear the full cost of the tax. They can't pass the tax increase on to consumers.

As the figure shows, local production of oil will fall by a small amount after the tax is imposed, which means that imports of oil will go up. The amount of this reduction depends on the elasticity of the supply curve. As usual, the supply response grows larger over time. Initially, there should be very little supply response, but over time, wells will be retired from service sooner and fewer new wells will be drilled.

What might the size of this impact be? One estimate cited by opponents of Proposition 87 is that local production will fall by an average of about 3.4% or about 22,000 barrels per day over the first 10 years of the life of the tax. Oil produced in California meets only 37% of consumption there. The balance is supplied by oil imported to California from Alaska and the rest of the world. This means that imports of oil into the state would increase by about 1.8%. A gradual increase in imports of this magnitude would be too small to have any perceptible effect on the world price of oil or the transportation costs of oil to California.

The local producers do understand the economics of tax incidence. Chris Hall, an oil producer based in Torrance, CA, was quoted in the San Diego Union-Tribune as saying of the tax that “I can't pass it on…I'm a price taker and not a price maker. I don't determine the market.” Understandably, these producers have raised a lot of funds to support a campaign to oppose the imposition of this new tax. The tax would raise up to $4 billion before it expires, so for oil producers as a group, it makes sense to spend millions of dollars to defeat the tax. What is interesting about the campaign ads that they support is their repeated claim that the tax will raise the price of gasoline. No doubt, their campaign consultants have found that raising this irrelevant issue is the most effective way to get people to vote against this proposition.

Reasonable people can differ about whether Proposition 87 is a good idea. See the

web page, by one well-known economist who studies energy, Severin Borenstein, for an even-handed discussion of its plusses and minuses. Or read

this critique by Greg Mankiw. Ironically, he is opposed to the proposed tax because it will not increase gasoline prices and therefore will not encourage conservation. This kind of discussion clarifies the issues and helps people understand the underlying economic principles.

The other kind of political discussion, the kind that goes on between battling pundits or in the back and forth of campaign ads, sways some voters because they don't have the benefit of an introductory course in economics. They don't understand something that you do: a tax on a small subset of firms in a competitive industry will not affect the price paid by consumers.

1. Greg Mankiw correctly points out that the tax in Prop 87 is not a Pigovian tax--that is, a tax on oil for the purpose of reducing oil consumption to socially optimal levels. However, the revenues from Prop 87 are intended to subsidize the research and development of alternative energy. Because the marginal private benefit of R&D is less than the marginal social benefit, the market does not allocate enough resources to R&D on alternative fuels. Appropriate government subsidies could encourage a socially optimal level of R&D. Does this mean Prop 87 is in fact a Pigovian subsidy? Should Mankiw and the other members of his

Pigou Club support such a policy? (Thomas Friedman and Al Gore, both of whom Mankiw counts among the membership of the Pigou club, already do. Other members of the Pigou club are encouraged to comment…)

2. Would a Pigovian tax on gasoline consumption be a better way to fund research on and development of alternative fuels? Why or why not?

3. How useful is it to enact public policy through ballot measures? On the one hand, polls show that the public isn’t well informed as to the economic consequences of Prop 87 and other ballot measures. On the other hand, the policies developed by legislators are also imperfect. Some people argue that elected officials face few political incentives to tackle long-term problems like global warming. Is Prop 87 an example of “direct democracy” achieving something the legislative process could not? Or is it an example of why setting public policy is best left up to the legislature?

Labels: Gas Tax, Price-taker, Taxes

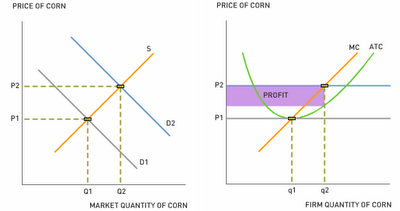

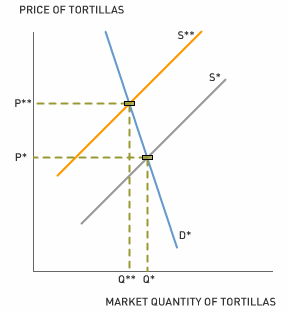

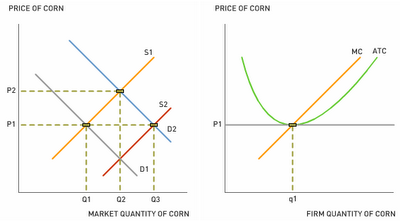

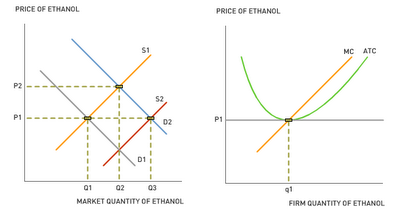

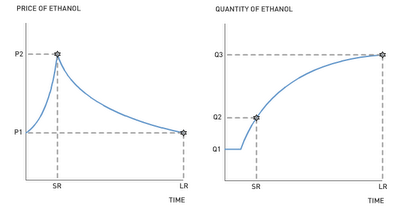

In the long run, the lure of profits attracts new ethanol producers. The long-run entry of additional ethanol producers expands the supply of ethanol, causing the price to fall back to its initial level:

In the long run, the lure of profits attracts new ethanol producers. The long-run entry of additional ethanol producers expands the supply of ethanol, causing the price to fall back to its initial level: Notice that economic profits converge to zero in the long run. As explained by most textbooks, zero economic profit does not mean that ethanol producers barely have enough to eat. Zero economic profit means that ethanol producers are earning incomes that compensate them for the next best salary they had to give up to go into producing ethanol.

Notice that economic profits converge to zero in the long run. As explained by most textbooks, zero economic profit does not mean that ethanol producers barely have enough to eat. Zero economic profit means that ethanol producers are earning incomes that compensate them for the next best salary they had to give up to go into producing ethanol. Discussion Questions

Discussion Questions