2008 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences

by Michael Enriquez The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences recently awarded the 2008 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences (PDF) to Paul Krugman of Princeton University. Krugman showed how economies of scale can help to explain patterns of trade and the location of productive activity. His research into international trade developed a new trade theory that explained trade patterns that previous theories could not. The model that he developed for international trade also became useful for analyzing economic geography.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences recently awarded the 2008 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences (PDF) to Paul Krugman of Princeton University. Krugman showed how economies of scale can help to explain patterns of trade and the location of productive activity. His research into international trade developed a new trade theory that explained trade patterns that previous theories could not. The model that he developed for international trade also became useful for analyzing economic geography.Before the publication of Krugman's seminal articles, international trade theory was dominated by the concepts of comparative advantage and factor-proportions. The former was due to the insights of David Ricardo, who emphasized opportunity costs as the basis for the gains from international specialization and exchange. Eli Heckscher and Bertil Ohlin further developed the theory by examining cross-country differences in factors of production as the basis for trade patterns. These traditional theories are good at explaining observed trade patterns between a developed nation and a low-income nation.

However, these traditional trade theories are not able to explain the vast majority of trade flows among developed nations. These trade flows, called intra-industry trade, involve trade within the same industries. Such trade does not conform to the traditional theories because opportunity costs and factor proportions are often similar in the nations that exchange products from the same industry. For example, automakers in the U.S. export cars to Japan, and Japanese automakers export cars to the United States. This can't be explained by the Ricardian concept of comparative advantage.

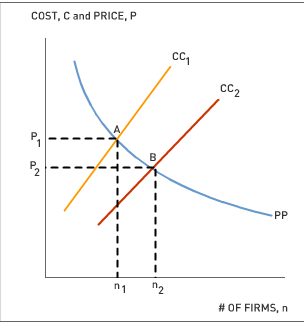

Krugman was awarded this year's Nobel Prize in economics in part because his models of international trade can explain such intra-industry trade as resulting from monopolistic competition, economies of scale, and consumer preference for product diversity. Krugman's model can be illustrated in a graph like the one above, which examines the relationship between the number of firms, the average cost of production, and product price in monopolistically competitive industry. Specifically, the CC curves represent the relationship between firms' average cost of production and the number of firms in an industry, and the PP curve represents the relationship between product price and the number of firms in an industry.

Recall that in a monopolistically competitive industry, firms produce products (like cars) that may differ in quality and style. As more firms enter a given market, each produces less, and average costs increase; therefore, the CC curves are upward sloping. At the same time, more firms mean more competition, which drives prices down; therefore the PP curve is downward sloping.

Where does trade come in? Well, suppose there are automobile producers in the U.S. and Japan. If there is no trade between the two countries, only a certain number of car types will be supported by the sizes of these two markets. But if the two countries can trade, then firms in both countries can sell to consumers in both countries, because some American consumers will prefer Japanese cars and vice versa. This increase in the size of the market means that the automakers are able to produce more cars at lower average cost by taking advantage of economies of scale. In Krugman's model, this causes the CC curve to shift from CC1 to CC2. Consequently, the market equilibrium moves from A to B, which results in a lower equilibrium product price, P, and a greater number of firms, n, producing for the industry. Consumers also benefit from a wider range of available product varieties .

Another important aspect of Krugman's work that was cited by the Nobel committee is the extension of his model to explain the location of economic activity, work that is credited with developing the field of economic geography. It helps to explain the core-periphery pattern of urbanization and migration seen in much of the world. Krugman also made noteworthy contributions to research on strategic trade policy and currency crises. Several pages summarizing his research are presented in the Nobel Prize committee's scientific background paper (PDF).

Discussion Questions

1. Paul Krugman is, for an academic economist, relatively well-known by the public due to his numerous television appearances, books, and articles in the popular press. Some academic economists have been critical of contributions that are easily accessible to the public. Do you believe that such less-scholarly work by Krugman detracts from or adds to the respect he has gained for the contributions which have earned him the Nobel Prize?

2. In what industries besides automobiles do we observe trade patterns which conform to Krugman's theory?

3. What are some of the drawbacks to globalization? Do you think that globalization has had a negative effect on your life, a positive effect on your life, or has had little impact on you? Explain.

Labels: Costs of Production, Free Trade, Gains from Trade, Globalization, International Economics, Nobel Prize

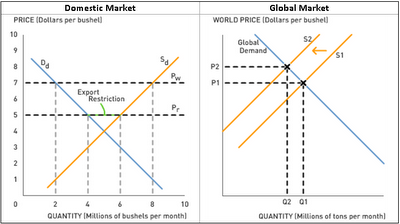

The export restrictions may have kept food prices down in domestic markets of major grain exporters, but from a global perspective, the restrictions undoubtedly prolonged the food crisis. As major grain exporters restricted the amount of grain leaving their borders, the global supply of grains declined, leading to higher grain prices and reduced availability in the rest of the world.

The export restrictions may have kept food prices down in domestic markets of major grain exporters, but from a global perspective, the restrictions undoubtedly prolonged the food crisis. As major grain exporters restricted the amount of grain leaving their borders, the global supply of grains declined, leading to higher grain prices and reduced availability in the rest of the world.