Leggo My Eggo! Really!

by Ben Resnick It’s hard to miss the barren shelves in grocery stores due to a pending Eggo Waffle shortage. The recent run on the popular breakfast food is one of the few times when a very clear-cut piece of microeconomics hits home enough to capture the attention of people without an economics background. What fascinates me the most about this story is how people with no interest in economics still have the shortage on the tips of their tongues. I believe there are two different microeconomics concepts at play here: one covered in nearly every introductory economics class and the other a deeper assumption that deserves more discussion than it normally gets.

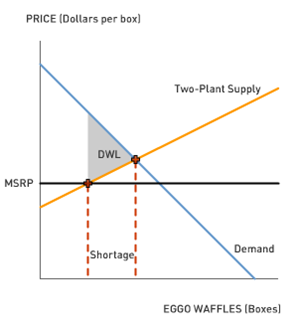

It’s hard to miss the barren shelves in grocery stores due to a pending Eggo Waffle shortage. The recent run on the popular breakfast food is one of the few times when a very clear-cut piece of microeconomics hits home enough to capture the attention of people without an economics background. What fascinates me the most about this story is how people with no interest in economics still have the shortage on the tips of their tongues. I believe there are two different microeconomics concepts at play here: one covered in nearly every introductory economics class and the other a deeper assumption that deserves more discussion than it normally gets.First, the shortage in stores essentially comes from Kellogg’s self-imposed price ceiling. It seems that Kellogg has decided to continue selling Eggo Waffles at the same manufacturer’s suggested retail price (MSRP) rather than raising it to reflect a decrease in supply since two of their four production plants are out of commission. By leaving the price where it is, there is a shortage in the market because more people would like to buy at the MSRP than Kellogg wants to serve. This decision seems odd to economists because it introduces inefficiency. The price ceiling creates a shortage in the market which leads to the inefficiency. On the corresponding graph, you can see the minimum amount of deadweight loss (DWL) in the market for Eggo waffles given this shortage; the DWL could be larger if those consumers with a lower willingness to pay are the ones who end up buying the existing waffles. One possible reason for the price ceiling is that Kellogg does not want to appear like it is trying to profit off of its own misfortune (the Atlanta plant closed due to heavy rain) and planning (the Tennessee plant closed for repairs).

Operating under typical economic assumptions, unless Kellogg or individual stores decide to raise the price, the shortage in grocery stores should continue. This means that some consumers who would be willing to pay more than the MSRP will be unable to get waffles. Which customers end up with the waffles will only be a matter of timing and luck, and it is very likely that some people who are unable to purchase waffles will value them more than others who buy a box they find on the shelves. One common explanation economists offer about how this situation will be resolved is the emergence of a secondary market or black market. USA Today interviewed Joey Resciniti, a shopper who bought one of the last boxes, who said, “I told my husband that maybe I need to put them on eBay." In secondary markets, people who are lucky enough to buy the boxes at the MSRP are able to turn around and sell them to an unlucky person who is willing to pay above the sticker price but was unable to buy any waffles in the store, exactly what Ms. Resciniti suggested.

The second economic concept at play here is the competitive hypothesis. The classic supply and demand analysis used above rests on some core assumptions of economics, such as rationality of agents, complete information, and the competitive hypothesis. When any of these assumptions are broken, we need a different model to understand what will happen in the world. The competitive hypothesis can be summed up by the assumption that a consumer believes that if they decide to buy a product they can afford, they are able to get it. For example, if I worried that the gas station near my house would run out of coffee before I get there in the morning, I might behave much differently. The same can be said of Eggo Waffle consumers. In the USA Today article, Ms. Resciniti also said, "We have eight of them, and if we ration those—maybe have half an Eggo in one sitting—then it'll last longer.” If consumers believe they will have a hard time finding an item they want to buy, they may instead chose to change what they want to buy. If for example, Ms. Resciniti does start to ration her waffles, then she may need to buy more oatmeal or fresh fruit for breakfast on other days. If consumers start rationing because the competitive hypothesis does not hold, a more complicated model is needed to correctly determine equilibrium behavior.

Discussion Questions:

1. What should the shortage of Eggo Waffles do to the demand for other brands of waffles? What about the demand for maple syrup?

2. Think of some secondary markets you are familiar with, like eBay, ticket scalpers, or craigslist. How are prices determined in these markets? If a secondary market for Eggo Waffles forms, what can you say about the equilibrium price?

3. If a black market for Eggo Waffles did emerge, who would be worse off at the equilibrium? Would anyone be better off?

4. Think of some other real-world examples where the competitive hypothesis is violated. What would need to be added to the basic supply and demand model to accurately predict what people do when they aren’t sure if the store will have the goods they want in stock?

Labels: Competitive Hypothesis, Market Failure, Price controls, Secondary Markets, Shortage