The Federal Reserve’s New Target Range

by Michael Enriquez On December 16, 2008, one of the most significant monetary policy decisions in US history was handed down by the Federal Reserve's Open Market Committee (FOMC). In an effort to combat accelerating deflation in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and massive job losses, the FOMC announced a reduction of its federal funds rate target from 1% to an unprecedented range of 0% to 0.25%. While critics of the move might point to relatively stable core inflation rates (which exclude food and energy), the FOMC was clearly more concerned about the state of the job market and the accelerating deflation reflected in the headline CPI. In fact, for two consecutive months, the US experienced record CPI deflation with rates of -1% in October and -1.7% in November of 2008. Along with OPEC's attempts to curtail oil production, this move by the FOMC is likely to help stabilize the price level.

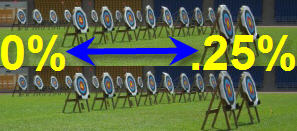

On December 16, 2008, one of the most significant monetary policy decisions in US history was handed down by the Federal Reserve's Open Market Committee (FOMC). In an effort to combat accelerating deflation in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and massive job losses, the FOMC announced a reduction of its federal funds rate target from 1% to an unprecedented range of 0% to 0.25%. While critics of the move might point to relatively stable core inflation rates (which exclude food and energy), the FOMC was clearly more concerned about the state of the job market and the accelerating deflation reflected in the headline CPI. In fact, for two consecutive months, the US experienced record CPI deflation with rates of -1% in October and -1.7% in November of 2008. Along with OPEC's attempts to curtail oil production, this move by the FOMC is likely to help stabilize the price level.The Fed announcement is historic for the low level of rates in its targeting and for the unique setting of a target range. This gives the Fed modest room for flexibility above the nominal floor of a zero federal funds rate. Whether it will be enough to spur the feeble economy is doubtful. Fortunately, the FOMC also announced that the federal funds rate is likely to remain within the target range for an extended period. The central bank is also prepared to purchase agency debt and mortgage-backed securities. Furthermore, through the Fed's expanded toolkit, it will begin direct loans to households and small businesses starting in 2009.

Fed chairman Ben Bernanke recognizes that the US economy is ripe for implementing the tenets of his Bernanke Doctrine, outlined in his 2002 speech titled "Deflation: Making Sure 'It' Doesn't Happen Here." In that speech, well before he was appointed to chair the Fed, he stated, "the economic effects of a deflationary episode, for the most part, are similar to those of any other sharp decline in aggregate spending—namely, recession, rising unemployment, and financial stress." Bernanke now has the chance to run the Fed during the precise scenario that he described six years ago.

In fact, the FOMC's press release of December 16, 2008 announces policy that effectively implements most of the seven steps of the Bernanke Doctrine. The FOMC's bold move may stave off a severe recession, but it does not come without potential costs. The combination of aggressive monetary policy, and recent and proposed fiscal stimulus could eventually reduce confidence in the US Treasury's ability to service its debts.

For the time being, Chairman Bernanke appears to be doing what is necessary to support another of his statements from six years ago:

Let me end my talk by abusing slightly my status as an official representative of the Federal Reserve System. I would like to say to Milton and Anna [Friedman]: Regarding the Great Depression. You're right, we did it. We're very sorry. But thanks to you, we won't do it again.

Discussion Questions

1. What could be the negative ramifications of implementing such a bold expansionary monetary policy at this time? How likely do you think it is that such negative ramifications occur?

2. Do you believe that historically low interest rates will be sufficient to save businesses struggling to avoid bankruptcy, such as those in the auto industry?

3. The current state of the US economy bears remarkable similarity to that of the beginning of the Great Depression. Do you think that Chairman Bernanke and his doctrine will keep the US out of a deflationary spiral? Will the doctrine, along with fiscal policy from recently elected officials, be enough to keep America out of a depression?

4. The US national debt held by the public is currently about $6.4 trillion or 45% of the nominal GDP in 2008. Is there any reason to worry over the ability of the US Treasury to meet national debt obligations? Why or why not?

5. Now that gasoline prices have returned to low levels, some economists may believe that it is an appropriate time to raise the federal gasoline tax. Do you agree with this position? Why or why not?

Labels: Consumer Price Index, Deflation, Global Economic Watch, Interest Rate, Macroeconomics, Monetary Policy, Recession