Digital Distribution Meets the Video Game Market

by Kasie R. Jean GameStop and EB Games have always been the major players in the used video game market when it comes to retail sales. Given their level of success, it was only a matter of time before other major players, such as Amazon.com and Toys "R" Us, entered the market. But how does this affect the long-term profitability of retailers, game publishers, and game developers?

GameStop and EB Games have always been the major players in the used video game market when it comes to retail sales. Given their level of success, it was only a matter of time before other major players, such as Amazon.com and Toys "R" Us, entered the market. But how does this affect the long-term profitability of retailers, game publishers, and game developers?The short-term motivation of retailers such as GameStop buying and selling used games is that they share none of the profit with developers of the game. Game publishers and developers only receive a payment for the sale of brand new games and are thus negatively affected by the growing used video game market, especially during bad economic times when sales are already lower than desired. Although buying used games instead of new titles might only save consumers $5-$10, some GameStop stores also allow you to return used games within 7 days if they don’t work properly or you simply don’t like the game, an option unavailable if you pay for a new game.

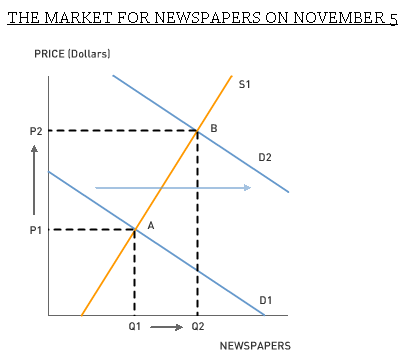

Incentives play a crucial role in economic analysis. Properly aligned incentives can promote desired outcomes in the short run and long run. From the perspective of video game developers, the lost revenue from video games trading hands multiple times in the used market is evident. As an increasing number of retailers realize the gains from entering this market, video game developers will experience decreasing gains from the production of new games.

This provides publishers with the incentive to consider other mediums of distribution, in particular digital distribution. The video game market is not the first entertainment industry to delve into a more technical solution. In the music industry, CDs are being replaced by iPods and MP3s thanks to Apple's iTunes. In the movie rental industry, we have gone from renting at our local store to mailing in movies through services such as Netflix or Blockbuster to downloading movies directly to our TV through the internet or cable services.

Therefore, it is not surprising that the video game market is heading in this direction, especially with the growing popularity of the used video game market. Since its inception, the Nintendo Wii has offered games from older consoles for purchase through the Wii Marketplace. Because the Wii offers free Wi-Fi, Nintendo can bypass the middle man of in-person and online retailers. In addition, Microsoft has begun to experiment with this option by offering smaller-scale, arcade-like games for purchase using Microsoft points that can be purchased in the Xbox Live Marketplace. They also offer free demos of newly released games in hopes of attracting additional sales. The drawback with Microsoft is their Xbox Live internet service is not free, so only users with a paid account can access these services.

Discussion Questions:

1. From the consumer perspective, what would your indifference curves look like for these two goods? Do you believe a used game is equally as good as a new game? How would this affect the demand for used video games?

2. What kind of incentives, if any, could a video game developer provide to GameStop to encourage them to sell new games over used ones?

3. How will the growing popularity of releasing and purchasing video games through an individual console change the market structure of video game retailers? How does this compare to the success of the iPod and MP3s in general?

Labels: Costs of Production, Game Theory, Preferences, Technology